.

by Carolyn Thomas ♥ @HeartSisters

I just love this. Which is to say I don’t love it at all – you need to imagine the snark in my voice if I were actually saying that out loud to you. What I don’t love at all is this example of a real life physician (a cardiac surgeon in Indiana) who is answering a patient’s online question on the website called HealthTap (a site that appears at first blush to be about medical Q&A, but is actually more like a matchmaking service between doctor-shopping patients and the doctors who want to woo them).

The patient asks HealthTap:

“What caused my arm pain during my recent heart attack?”

And the cardiac surgeon replies to the patient (let me repeat that, because it’s critically important to our story) TO THE PATIENT:

“The pericardium is innervated by C3,4,5 (Phrenic nerve). There may be some neuronal connections to the intercostobrachial nerves.”

Oh, please. . . My follow-up question to this cardiac surgeon would be something like:

“Are you frickety-frackin’ kidding me?”

.

A distressingly large number of people who have the letters M.D. after their names actually say these kinds of things out loud (or online if you’re on HealthTap) to those who have never been to medical school (a.k.a. “patients”).

And worse, even patient education materials made available to those needing to learn more about a specific medical condition can be so jargon-heavy that it makes such material virtually useless to the average patient. Online resources can be even more confusing.

That’s what New Jersey researchers led by Dr. Charles Prestigiacomo found when they used a number of readability scales to test materials published by 16 different medical specialty societies, specifically looking at how challenging these materials were for patients.(1)

Easy readability is important, particularly for health messages, because their complexity can be an impossible barrier for those of us among the great unwashed who need this information. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly nine out of 10 adults have difficulty following routine medical advice, largely because it’s often incomprehensible unless you’ve been to medical school.

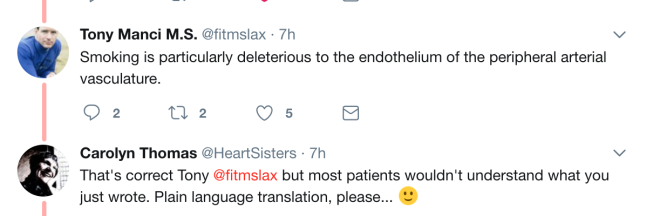

Medical jargon is not unique to physicians, of course. All kinds of health care professionals whose job includes communicating important information to their patients can sink into this jargon trap. Consider this Tweet from Clinical Exercise Physiologist Toni Manci in Milwaukee, and my resulting plea to him for plain language, for Pete’s sake.

And those who have been to med school are not immune to being baffled by medical bafflegab, as neurologist Dr. Richard Senelick found out when he accompanied his wife to a medical appointment. He wrote:(2)

” As my colleague rattled off a detailed explanation of ‘pH, calcium metabolism, oxalate ratios and the effect of citrate,’ I realized that even I didn’t have a clue what he was talking about.

“Unfortunately, like most patients and families, I didn’t want to show my ignorance, so I sat quietly and nodded my head. As we walked to our car, I was unable to explain the results to my wife. I did not have a clue.

“I was the poster boy for the fact that inadequate ‘health literacy’ is not restricted to the poorly educated.”

That’s why an increasing number of government agencies are now pushing public health professionals, doctors and insurers to simplify the language they use to communicate with the public in person, in all patient handouts, medical forms and health websites.

My favourite readability scale used in the New Jersey study, by the way, has been in use since 1969 and is called “SMOG grading” – which stands for “Simple Measure Of Gobbledygook”.

Now, that I DO love!

In fact, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh suggested in 2010:

“Web developers should consider routine monitoring of content readability with SMOG to increase the accessibility and ease of comprehension of online consumer-oriented health care information.”

Dr. Ivan Oransky reported on the New Jersey study recently in Pacific Standard magazine, in which he wrote:

” The average reading level of the online materials by groups ranging from the American Society of Anesthesiologists to the American Psychiatric Association fell anywhere from ninth grade to the sophomore year of college.

“That’s far above the fourth-to-sixth grade level recommended by the American Medical Association and by a number of government agencies.”

In an ironic and unintended example of what the researchers were highlighting, one of the study’s authors told Reuters Health:

“ We might not be cognizant of the population reading our articles, who might need something more simple.”

Okay, according to my own unofficial SMOG grading system, using words like “cognizant” immediately identifies you as a person who is not cognizant of the population reading that statement. Or, as one of my former editors liked to say:

“Never use a twenty-five cent word when a nickel word will do!”

As study author Dr. Prestigiacomo said in his interview with Dr. Oransky, using simple analogies can be an effective way to cut through the clutter of scientific jargon to make medical information easier to understand. For example:

“There are only so many ways you can describe an aneurysm. I tell patients such ballooning blood vessels are ‘like a blister on a tire.’

“The problem is that it’s not quite perfectly accurate. But sometimes we have to realize that simplifying it to an analogy may be the best way for patients to understand it.”

(Speaking of cutting through the clutter of scientific jargon, heart patients reading this might want to visit my patient-friendly, no-jargon glossary of common cardiology words, phrases and abbreviations).

Dr. Oransky also quotes Dr. Lisa Gualtieri, a Harvard-trained assistant professor at Tufts University School of Medicine. She teaches courses like Online Consumer Health and Digital Strategies for Health Communication. Her take on the New Jersey study:

“The organizations represented should be happy that people are visiting their websites. It’s high-quality, reliable information, and there’s a lot out there that isn’t.

“But they often use jargon. They end up using the language they’re accustomed to as opposed to (the language) the people they’re trying to reach are accustomed to using.

“You have to think about reaching people where they are.”

Dr. Gualtieri also told Reuters Health that she recommends that those who produce such materials consider why people are coming to their sites in the first place, and what they’re looking for. She echoed the study authors’ suggestion that such sites also use pictures and videos.

Remember Dr. Richard Senelick and his story of being stumped by medical jargon during his wife’s appointment? Here’s his very useful list of tips on how to get your own doctor to stop using jargon:(2)

- If you do not understand what your doctor is saying, immediately stop them and ask them to use simpler language. Don’t pretend that you understand when you do not.

- Be assertive, but friendly. Let them know if you still have questions.

- Tell the doctor what you think they said to be certain that you understood them. This is called a “teach back.”

- If you feel you need more time, ask to schedule another visit in the near future.

- If the doctor is very busy, ask if there is a nurse or assistant who can answer your questions.

- Take a friend with you for another set of ears and always take notes.

- Ask who you can call if you still have questions when you get home.

.

(1) Charles Prestigiacomo, MD et al: “A Comparative Analysis of the Quality of Patient Education Materials From Medical Specialties.” JAMA Internal Medicine. May 20, 2013.

(2) Dr. Richard Senelick, MD: “Get Your Doctor To Stop Using Medical Jargon”. Huffington Post. April 25, 2012.

This article was also picked up as a guest post by The Center for Advancing Health’s Prepared Patient Forum.

♥

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote much more about communicating with your health care professionals in my book, A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease . You can ask for it at your local library or favourite bookshop, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon, or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

.

Q: Have you been the target of medical Gobbledygook?

.

See also:

Patient engagement? How about doctor engagement?

When doctors use words that hurt

Emotional intelligence in health care relationships

Why don’t patients take their meds as prescribed?

I’m not a fan of jargon but I’ve also seen my share of patient information that is so simplified and generalized and sugar-coated as to be almost useless. There are risks when people hear information that sails right over their heads, but there’s also a risk in consistently dumbing it down to the lowest common denominator.

Can’t there be a happy medium?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for bringing up an important point, Anne. There MUST be a happy medium between being incomprehensible and being baby talk (like doctors who – seriously – refer to a patient’s heart as “your ticker”.

LikeLike

It’s great to see you here, Anne!

I agree. I think there can be a happy medium, drawing from my experiences. I think part of the problem is that all patients have different levels of health literacy, interests, needs and goals. These need to be identified before appropriate and important discussion can begin.

Awesome post, Carolyn! As I Tweeted you, the issues of language you explain here remind me of the play and film Wit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment here, Ashley. “Wit” is a must-see film starring Emma Thompson – the fictional story of a university professor who is dying of ovarian cancer.

LikeLike

Didn’t you recently do a post on why your arm hurts during a heart attack? I seem to remember reading and understanding the mechanism when you said it. Doctors need universal translators (Star Trek reference) and should tailor the answer to the audience. The “teach back” is crucial for comprehension. After developing atrial fibrillation, I developed a whole new vocabulary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, good memory, Allison! I did write a post on arm pain during heart attack (which was how I happened to stumble upon the doc’s unintelligible HealthTap quotation!) The difference between my explanation and his was that I was speaking English, while the good doctor was speaking medicalese.

LikeLike

SMOG grading…Laughing in Virginia, Carolyn.

The new ‘health care’ changes have many providers twitching and acting out towards US patients. Years ago, sent to a male oncology hematologist for unremitting acute anemia, he used the phrase “normal menstrual bleeding should be around so & so mg/dls. I just stared at him, said “You can’t seriously be talking to women like that. Your specialty is BLOOD and all females do is bleed for decades. Talk in soaked pads/ tampons. Period!” He turned beet red and agreed…admitted he had never thought of that before. What the?????

No room for your embarrassment at this level (and expense) of treatment. Please ‘talk turkey, doc’. I asked my female ob/gyn the same question later to be fair & balanced.

I always include ‘female’ info w any doc I see for cardiac treatment because it is completely intermingled w female heart health and function. Always appropriate.

Thanks for another article chock full of terms for me to google.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I too love that SMOG grading tool! When your hematologist “turned beet red and admitted he had never thought of that before”, that says a lot about our medical education system, doesn’t it? It means that students are graduating med school without being trained to even think like a patient, never mind speak coherently to one. I guess I shall continue banging my drum here until somebody hears us . . .

And very good point, by the way, about ‘female info’ – I had preeclampsia during my first pregnancy (linked to a 2-3 fold increase in increased risk of later heart attack). Nobody knew that at the time. Fast forward 30 years to my MI: every doctor who treated me wanted to know about my family history, smoking, diabetes and other possible risk factors to explain how a distance runner like me with “normal” test results could have an MI. Not one of them asked, then or since, about any pregnancy complications. All intermingled, as you say. Thanks for your wisdom here, Jaynie!

LikeLike

Carolyn,

Again, you expose complex problems in a truly accessible way. We too have blogged about the harmful effects that can result when doctors are unaware of tone and word choice. In many cases, doctors are pressured for time and not listening carefully, asking the right questions, or even making eye contact! In turn, patients are left feeling uneasy, stressed, and prone to “doctor shopping” — none of which contributes to good health.

The medical explanation posted on the HealthTap website is certainly unintelligible. But it is also a powerful statement that a doctor can offer an opinion in the first place without meeting or examining the patient. My grandfather Dr. Bernard Lown always says, “The individual patient is invariably the exception to the statistic.”

-Melanie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Melanie and thanks for sharing this. That issue about docs not listening or even making eye contact makes me cringe when I think of all the hype among some MDs for coming tech distractions like Google Glass, in which the doctor’s eyes will be flitting skyward nonstop to check the tiny computer screen above his right eye – instead of looking directly at the actual patient who’s right in front of him.

And those HealthTap Q&As are not even remotely designed to really answer patients’ questions, as you can plainly see, but instead to attract ‘votes’ from other docs to increase individual rating appeal to those doctor-shoppers. A discouraging trend…

LikeLike

Hi Carolyn,

Your article is so important and coming from a healthcare consumer makes the impact even more significant. I just wanted to send you the reference for one of the articles you cited. It is in the July 8, 2013 JAMA Internal Medicine.

Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Sabourin V, Tomei KL, Prestigiacomo CJ. A Comparative Analysis of the Quality of Patient Education Materials From Medical Specialties. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1257-1259. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6060.

LikeLike

Thanks Mary – I had already included that reference at the bottom of my post.

LikeLike

During his medical residency, my husband took a call in the middle of the night. This is what I awoke to: My husband’s side of the conversation…

“Did he urinate?”

“Has he urinated?”

“Did he go pee?”

He learned very quickly not to take anything for granted!

We still get a chuckle out of this…

Joan

LikeLike

Oh, Joan – I’m laughing out loud at this. Thanks for this priceless example of jargon-free communication! 🙂

LikeLike

I usually understand what my doctors are saying, but sometimes I fail to catch it fully. I have moderate hearing loss, and must pay close attention and look at the person who is speaking. However, this proves to be a problem with doctors who have accents. I just do not pick up the sounds the same way. Unfortunately, 3 of my doctors have foreign accents and, while I like them very much, the above situation presents a problem for me.

LikeLike

Thanks Pauline. This is an important issue. Dr. Senelick’s advice is especially useful: for example, don’t pretend that you understand if you don’t, and repeat what you think you heard to make sure that information is correct. Raise your hand to interrupt them as soon as you realize you’re not ‘getting it’, and don’t be shy about asking them to repeat, or to speak more slowly.

Don’t ever leave any doctor’s office feeling confused about what was just said to you. Docs need to know that – whether it’s an accent or the speed at which they speak or the medical mumbo-jumbo they’re using that is getting in the way, it is THEIR responsibility to communicate clearly.

LikeLike

OMG, Carolyn! This just happened to me Thursday! Even with my high level of university education AND my (unfortunate) high level of medical system training by being a chronic illness patient, I had NO clue what this doctor was saying.

He handed me a pamphlet to read while he disappeared for a few moments and I was no more illuminated than if I’d stared at a blank wall for 10 minutes.

When I tried to repeat back and ask questions I got the lovely ATTITUDE of “that is not what I said” and “read the pamphlet” and then he had the actual guts to say – don’t come back for two weeks even if it gets worse and I will be on vacation.

Absolutely unbelievable !

JG

LikeLike

Unbelievable, indeed, JG. I hope this man is now your EX-doctor. He wasn’t, by any chance, that Indiana cardiac surgeon who answers patients’ questions on HealthTap . . .?

LikeLike

I frequently say to patients: “Now I am going to translate from medical into English.” Having patients “read back” or explain what I have just told them helps, too. What I also know is that in a doctor’s office, especially when hearing a frightening diagnosis, people CAN’T hear what I am saying because of emotional upset, shock or denial. So an extra appointment or extra time with another office staff person really helps.

LikeLike

You are right on the money, Dr. S! Emotional shock and denial can make us both blind and deaf when our doctors are speaking ‘medical’ to us. I know that when the cardiologist was called in to the ER during my heart attack, I could see his lips moving and I knew sounds were coming out of his mouth after he said the words “significant heart disease” to me, but he might as well have been speaking Swahili by then. Thanks so much for your perspective on this.

LikeLike

Emotional shock: Another good reason to take along a trusted friend or family member with you who will take notes and ask questions. We even audiotaped (with doctor’s permission) the doctor’s description of the testing results and treatment plan so we could replay later and “digest” everything. The recording also helps to learn the ‘language’ associated with your illness.

LikeLike