by Carolyn Thomas ♥ @HeartSisters

I vaguely recall my gurney being wheeled very quickly down a wide hospital corridor after I heard the words “heart attack” from the cardiologist who had been called to the E.R. I stared up at the ceiling lights flicking by overhead, feeling freakishly calm, considering. Here’s what I recall thinking in my strangely calm state: when I’d first come into this same E.R. two weeks earlier, terrified that my symptoms of chest pain, nausea, sweating and pain down my left arm might be due to a heart attack, I had been right!

I vaguely recall my gurney being wheeled very quickly down a wide hospital corridor after I heard the words “heart attack” from the cardiologist who had been called to the E.R. I stared up at the ceiling lights flicking by overhead, feeling freakishly calm, considering. Here’s what I recall thinking in my strangely calm state: when I’d first come into this same E.R. two weeks earlier, terrified that my symptoms of chest pain, nausea, sweating and pain down my left arm might be due to a heart attack, I had been right!

The symptoms had never been because I was “in the right demographic for acid reflux” (despite what the Emergency physician who’d sent me home that first day had confidently pronounced). But now, after two weeks of popping Gaviscon like candy for these increasingly horrific symptoms, I felt relieved. I knew that all of the people around me now would know how to take care of me. The shock of hearing my new (correct) diagnosis of heart attack was subsumed in that moment by a wave of profound relief.

Q: How could anybody feel relieved when getting such a serious diagnosis?

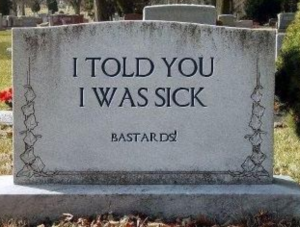

Turns out that there is one kind of patient for whom relief might be a common reaction: if you’ve been misdiagnosed, or spent any length of time wondering why the worrying symptoms you’re experiencing are being repeatedly dismissed as “normal”, finally hearing an accurate diagnosis can feel like a relief.

Sharon Roman had her own first debilitating symptoms at age 30. As she wrote in the BMJ about hearing her own life-altering diagnosis of multiple sclerosis:

“A diagnosis can be a revelation to patients. The pieces of the puzzle finally fit to form a picture. It brings a sense of relief; they have not been imagining or exaggerating their various symptoms. Although it’s a short-lived relief, as other emotions begin to tumble into the now vacant space: fear, anger perhaps at having felt trivialized, and more. It may even bring a sense of closure to the vicious game of chase with an unknown ‘it.’ At last, they are believable.”

For those who have been misdiagnosed, who know that something is terribly wrong, who fear that nobody will be able to help relieve their suffering, an accurate diagnosis is indeed a relief because without it, there can be no treatment plan.

It was a phone call that brought a serious diagnosis to Betsy Ahlers, a nurse who wrote about waiting for her test results to come back:

“It was a double-edged sword. Either I would get a diagnosis, which I wanted but would still be scared, or the test would lead nowhere, not be definitive, and leave me still searching, still not knowing.

“After a long week of waiting, the labs came in and I received the call. Even though it wasn’t a surprise, I was shaky and shell-shocked. And relieved. I cried. Not because I had something, but because I had something.There was a reason — a proven medical diagnosis to explains all my bad days, pain, symptoms.

This time, I didn’t hear, “Sorry, we don’t have an answer.” This time, they knew. And now I know.“

It’s important to keep in mind that feeling temporarily relieved – especially if an accurate diagnosis has been a long time coming – doesn’t ever minimize the reality of that diagnosis. With a chronic and progressive illness like heart disease, it can mean a significant adjustment to this diagnosis and then to a whole new way of life. (See also: The new country called Heart Disease)

It may come as a surprise to some physicians that relief can actually be one of the initial responses to this news. Here’s my favourite example of this: when I worked in hospice palliative care, twice a year our physicians taught an intensive one-week course to other health care professionals on end-of-life care. A very popular topic was called How To Break Bad News. One of the course instructors told us this story about his earliest experience as a young doctor charged with delivering a diagnosis of brain cancer to a patient. He felt nervous as he approached the woman waiting quietly for him in his office. He wasn’t sure exactly how to say this, or what to expect from her after he said it. Somehow, he screwed up his courage and managed to get out the bad news as best he could, but was shocked when the woman smiled, stood up from her chair, and gave him a hug. “Thank you!” she said. “I was convinced that you were going to tell me I was losing my mind!”

Whether a diagnosis is met by relief or by despair, continuing this doctor-patient communication about the diagnosis as kindly and thoroughly as possible is important because relief can quickly morph into fear as reality sinks in.

Clarice Bromley recalls how relieved she felt after years of suffering severe symptoms that turned out to be a rare hereditary connective tissue condition known as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. That relief was only temporary:

“I remember when I finally got diagnosed by a rheumatologist, I sat there and cried in relief. But for anyone searching for a diagnosis, please do not rely on that diagnosis as the be-all and the end-all of your problems, like I did. Of course diagnosis opens other doors to be investigated, but having a diagnosis didn’t make things any easier.”

Are you a healthcare professional who has to break the bad news of a serious diagnosis? Sharon Roman has this helpful advice for you:

“It’s worth remembering that your words and this moment will last a lifetime, so make the effort. You can never take back this one time, this life-changing moment for the patient.

“While it may have been a long day for you, it will be an even longer one for your patient.

“On the phone, please dial my number yourself, be the first voice I hear, and have my file already in front of you. If you are cold and hard, the news will be harsher.

“In person, be mindful of your body language and soften your words with your posture. Before you utter a sound, think about what you are saying to your patient and where you are saying it from. As busy as you may be, don’t let being rushed show. If the setting allows, come back to check in before you leave; you can be a constant in a new world of uncertainty – even if it is for just one day.

If you are referring a patient, assurance in the new doctor goes a long way. Let them know that they will be in good hands. Write down the name of the diagnosis (“I have a what . . . ?!”). Have some information at hand, if possible, along with a list of reliable resources for more information. Offer the name of an organization that can offer links to support groups and other trustworthy, helpful sources.

“I don’t need a hug, but I do ask for solicitude and compassion. I am more than just a patient. I am a person, a daughter, a wife, a sister, an aunt, and a friend.”

(Carolyn’s note: Docs, please tell your female heart patients about WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease; they offer a large 24/7 online support community, in-person local support groups, and scheduled virtual support group meetings. All are for any woman living with any form of heart disease, and are free to join).

♥

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote much more about both getting and offering support in my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease”. You can ask for it at your local library or favourite bookshop, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon, or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

.

.

Q: Has an odd sense of relief ever been your reaction to hearing a diagnosis?

.

See also:

How we adapt after a heart attack depends on what we believe the diagnosis means

My medical diagnosis means more to me than to you

When a serious diagnosis makes you feel mad as hell

Looking for meaning in a meaningless diagnosis

Heart attack misdiagnosis in women

.

PLEASE READ THIS: I am not a physician, so cannot advise you if you’re having symptoms. The information on this site is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice. Please consult your doctor for specific help.

I’ve heard some nasty horror stories of people’s healthcare professionals not diagnosing Ehlers-Danlos or not treating it properly. It seems to me one of those cases where if you have non-specific symptoms or are in the “demographic” of a minor ailment, as you say, the risks of doctors not communicating properly or being receptive to communication go way up. I don’t know what it is, but it’s really unfortunate. Then when you have a decent appointment, it’s relief. No more strategizing how to get a doctor to… be a doctor.

(Smacks forehead.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an important point, Ashley. I think that, by the time a person feels sick enough to seek medical help, the expectation is certainly that ‘this doctor will help me.’ It can, oddly, be a blow to hear that not only will this doctor not be helping, but the complaint might be dismissed…

LikeLike

It’s an all too common occurrence – misdiagnosis -… So relieved every time I hear that someone finally found someone to listen and believe the patient. I too know this feeling – after months of severe pain in my chest – one doctor – was able to believe me and took me at my word. That Dr. Troulakis saved my life. Hopefully, these changes will continue to happen for others who are suffering and waiting for the help they need.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yikes. After MONTHS of severe chest pain??! I wish there were many more doctors like Dr. Troulakis… So glad you found a good one!

LikeLike

I was much younger only 46 years old at the time, not overweight etc. I was 47 when I had open heart surgery. Atrial Myxoma :)… Lucky! I still see him after 20+ years..

LikeLike

Wow. I understand that it’s mostly women who have myxomas. How nice to have the same cardiologist for 20+ years. I hope to say the same thing someday!

LikeLike

Perfect post!

I distinctly remember being abjectly disappointed every time a diagnostic test for yet one more horrible disease came back and the doctor looked through me with the news it was negative.

There is not only a sense of relief but a sense of vindication when a diagnosis is made. Unfortunately, the relief of being able to name the “malady” is quickly replaced with learning to live with it or in many cases die with it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Judy-Judith! It may sound weird to some people to feel disappointed when a diagnostic test for a “horrible disease” comes back negative, but I totally get that!! That negative test means “we don’t know”, so how can anything be done to help if they don’t know? You’re so right – that sense of vindication/relief is usually temporary…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really like this post, too. Vindication is the perfect word for the feeling! I’m fortunate in that my most challenging condition is crystal clear on scans, even to laypeople. There’s so much trouble with subjectivity and interpretation… And it’s also crystal clear how it would affect someone who has it, so I don’t have to defend myself there either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are fortunate, Ashley! There’s also a risk, however, that sometimes even diagnostic test results that point to only one conclusion are often misinterpreted. I’m thinking here of Alicia Burns who lives with an often-fatal inherited heart arrhythmia called Brugada Syndrome. Brugada has a very distinctive EKG reading that can mean only one thing, yet as Alicia wrote about her FOURTEEN YEAR nightmare of having her EKGs ignored: “Cardiologists had seen these abnormalities on my EKG, but since all other cardiac tests were ‘normal’, they wrote it off.”

So a patient not only needs a primary diagnosis that’s easy to identify on tests, but she also needs physicians who are capable of recognizing the test results!

LikeLike

My diagnosis of heart disease came slowly over the course of weeks. My family doctor referred me to a cardiologist when I told her about the tightness in my chest and difficulty breathing that I had been having for some time. I resisted the recommendation to do a stress test but after consulting with the cardiologist was convinced that we should do it. I was overweight and out of shape but felt that I could deal with that myself. I began to change my thoughts when the cardiologist said, “Out of the five main risk factors for heart disease, the only thing you’ve got going for you is that you don’t smoke. You have type 2 diabetes, you’re overweight, you don’t exercise and you have a family history of heart disease.” Then she told me that she didn’t just want a stress test, she wanted a stress echocardiogram.

During the test, I walked for about 3 minutes and was absolutely gasping for breath. She was really concerned because “you don’t walk well.” But the images she got weren’t conclusive so she told me she wanted to do a cardiac catheterization within the next two weeks.

I think that was when it began to sink in that something must be terribly wrong. Still, I hemmed and hawed about it to the point where she suggested I have a talk with her nurse practitioner who would answer all my questions. By the time I got to that appointment I had thought it through and knew I should go through with the cath. The pieces of the puzzle were falling into place for me at that point.

And so it was with mixed feelings that I received the final diagnosis on the cath table that yes, there was a blockage and they were going to insert a stent. A feeling of relief came when I realized I had not gone through all this for nothing — there was really something wrong — and they were going to do something about it. But I was still afraid of the procedure and had no idea what to expect after it was all over. What did this diagnosis of heart disease mean for my future?

I think feeling very confident in my doctors was a huge help through all this. My cardiologist was sensitive in the way she quietly convinced me about what was going on and what was needed. The nurse practitioner is so easy to talk to, and she took a long time with me to explain everything thoroughly. The interventionist was a short, dynamic, energetic doctor who was obviously in complete control of his team. He even yelled at me when I tried to raise my head to see the images as I was lying on the table — but I really liked this doctor anyway. And there was one gentle, compassionate nurse who assured me she would stay right with me through the whole thing, and she did, periodically stroking my forehead and telling me, “You’re doing great. You’re doing great.”

I went through a second cath just about a year ago and they found a second blockage in the same artery (LAD) and I received another stent. The second time was actually a lot harder, for a lot of different reasons. I went through rehab both times and that was harder the second time too.

I believe that a firm diagnosis is a great thing, no matter how devastating. You can’t fix what you don’t know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So SO true, Meghan! “You can’t fix what you don’t know!” And yet so many of us would behave just as you did (wanting to procrastinate on getting diagnostic tests or procedures even when our doctors are recommending them!) It’s like thinking that if we don’t go in for this test or scary procedure, maybe it will all go away? You’re getting to be an expert in having stents implanted in your LAD (just what nobody wants to be, right?) Take good care of yourself…

LikeLike

Two years ago a male cardiologist told me my chest pain was “anxiety,” after spending five minutes with me. I sought a second opinion at a women’s health center and the female cardiologist, after speaking with me and finding out that I also had migraines and Raynaud’s, made the correct diagnosis of Prinzmetal’s Angina and started me on the correct medication.

In January of this year I went to a male GI with nausea, abdominal pain and weight loss. He looked at me over the computer and said that he sees from my chart that I have a history of “emotional problems.” I’ve suffered from depression and anorexia. He said that 80% of women who come in with nausea – it turns out to be nothing, while with men it usually turns out to be something.

Everything got really bad a couple months later and I went to a female GI at the same women’s health center. I was diagnosed with SIBO (small intestine bacterial overgrowth) last week after losing almost 20 pounds. Last time I was at this weight, I was on an inpatient eating disorder unit for 30 days, and was made to gain back 20 pounds. I feel like crap.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank goodness you decided to seek that second opinion! And also that your second cardiologist was so knowledgeable about Prinzmetal’s (which can be tricky to identify). I’m so sorry you had to wait so long for your new diagnosis – hang in there and feel better soon…

LikeLike

It is as though experiencing even situational anxiety – which should not be termed that, for various reasons, or depression, is the most heinous crime a human can “commit.” Those of us who are profiled as having “emotional problems,” when we present with objectifiable, measurable symptoms, need a hotline to call when we are “accused” of being nuts, rather than that the problem is that, metaphorically, (or otherwise), our arm is detached from our shoulder.

This hotline would bring the world’s foremost authority, M.D., J.D. PhD. with Board Certifications in everything, to the office or Emergency Department within moments. This super-expert would have the power to immediately remove the accuser from all medical practice anywhere on the planet, and either proceed with fixing the “arm”, or bring in a provider who would do so, without any of the psychic overtones, except that, they, unlike the pseudo-psychiatrist judge-doctor, would be of such humanity and experience that he or she would, of course, understand that, yes – when your arm is hanging off your body, if you don’t have some degree of anxiety, or, truer, “fear,” “fear” being a matter of knowing that you are in deep – ah – mud, and not treat you like a nutcase.

Should the case be, however, that you have finally slipped your moorings, in addition to having your “arm” detached, an actual, practicing, (not solely pill-dispensing), psychiatrist would be called in, not because your “crime” of an emotional imbalance placed you on the level of ax-murderer, (unless you ARE an ax-murderer – which calls for a vastly different approach), but because you are human. A shrink on the order of the best-known, yet fictional, psychiatrist of all time, Major Sydney Freedman, the beloved character from the television show, “M.A.S.H.”

Referencing the trauma of war, the impetus that brought Sydney into the picture, is not a great leap. Women are traumatized whenever their very real physical problems are dismissed and they are given a psychiatric label. Sydney wouldn’t do that. Why are so many physicians dedicated to it.

We do become calm when we receive a diagnosis after chasing symptoms, as, apparently, there is no greater crime than to be “nuts.” Whether it is chasing down chest pain, or breast pain, (there is never any pain associated with a breast cancer – go ahead, ladies, laugh your arses off at that one), we want to think we have been given a reprieve, both in terms of being able, at last, to identify and work toward the resolution of a symptom, (or make a plan), even if the reprieve is brief.

LikeLike

This was a very wonderful and well written post! My mother actually had a heart attack about 9 years ago. It was terrifying. She had double bypass surgery. It is truly amazing what we can learn to deal with in life and the strength we all have, that is sometimes hidden.

I have been battling Multiple Sclerosis for 16 years now and it has had its ups and downs, but I try to hold onto my positive attitude. I started my blog 2 months ago and it has been a great experience. I have been able to communicate with so many wonderful and amazing people that really understand what I go through. I look forward to reading more of your posts! Take care!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Alyssa – I hope your mother’s doing much better these days. You are so right – sometimes we don’t know the depths of our resilience until something catastrophic happens.

I love your blog (and especially enjoyed that sweet story – and photo! – of your hubby proposing to you onstage with your favourite band!) Thanks for taking the time to leave your comment here, and best of luck to you…

LikeLike

Thank you for your sweet comment! My mother is not doing all that great. She has been battling some horrible demons. She has or had a battle issue with alcohol and it has caused her so many issues. She actually has court on Thursday, I am only hoping for the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I’m so sorry to hear that. Hope Thursday goes okay…

LikeLike

Thank you so much! It is out of my hands now. I hope if you are following my blog, I will be able to provide something helpful for you! Take care and thank you for your kind words!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome…

LikeLike

When, finally and at very long last, my PCP sent me to a cardiologist, he asked me how I was. I replied, “I think I’ve got a problem, but I can’t prove it.” He said, “You’re right. You do have a problem, and it’s called microvascular heart disease.” He went on to explain what a sneaky form of heart disease this is, and how it can affect every individual in a different way; what danger signs to watch out for and how to cope with the MVD’s manifestations. All this happened almost 7 years ago. I am still saying “Thank God! Now I know!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is a very smart and well-informed cardiologist you have there, Sandra! Too bad it took you such a long time to get to see him, no thanks to your PCP. Not too long ago, I heard from one of my blog readers who told me that her own doctor had said to her: “I don’t believe in microvascular disease!” (as if they’d been talking about Santa Claus!) You, on the other hand, have a keeper…

LikeLike

When you finally get validation in a correct diagnosis, it brings a sense of calm because you knew something was wrong but they could not identify it. YEA, I WAS RIGHT! It took almost 30 years to get it right for me. Vindication! Once that was accomplished then everything fell into place and treatment was appropriate. Finally.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sharen – 30 YEARS?!?! That is impossibly awful! No wonder you felt both validation and vindication after all that time…

LikeLike

Carolyn, at the age of 20 I was having BP of 120-140/almost 200. Stroke levels and Constant headaches of migraine strength. For about 8 years, I could not lay down at night to sleep. I had to sleep sitting in a recliner. Left arm pain, horrific heartburn, trouble breathing, pain in right arm, neck, teeth, under shoulder blades. I was diagnosed with everything but what it actually was. Finally, after my Father died of a heart attack, I got a referral to a Cardiologist. I had to fight my way through visits with him until he did a thallium stress test and then a heart cath. Then he believed me. I was angry for years.

LikeLike

What a story, Sharen. And you were SO young when your symptoms began. I think it’s so awful that you had to “fight” all that time to get an appropriate diagnosis. No wonder you felt angry. How did you finally make some kind of peace with that?

LikeLike