by Carolyn Thomas ♥ @HeartSisters

Imagine your mechanic telling you that your brakes are failing. Would you voluntarily get behind the wheel of that car – and then happily drive it home? Of course you wouldn’t. Yet right now, as you are reading these words, doctors around the world in a medical office or hospital clinic somewhere out there are casually saying out loud the words “HEART FAILURE” to diagnose people who will leave that place feeling scared to death. .

Imagine your mechanic telling you that your brakes are failing. Would you voluntarily get behind the wheel of that car – and then happily drive it home? Of course you wouldn’t. Yet right now, as you are reading these words, doctors around the world in a medical office or hospital clinic somewhere out there are casually saying out loud the words “HEART FAILURE” to diagnose people who will leave that place feeling scared to death. .

Once a physician tells you that your heart is failing, you cannot unhear that word. You’re also unlikely to hear any other words being spoken about your diagnosis. You may hear sounds coming out of that doctor’s mouth, and you may see lips moving, but there will be limited comprehension while you sit there, stunned, clutching your failing heart.

And when such frightening words finally do sink in, the effect on patients is far more demoralizing than motivating.

Let’s consider these assorted definitions of what the concept of “failure” actually means in real life (i.e. not in medical school):

- the state of not functioning (e.g. engine failure)

- inability to pass a test (failed algebra)

- catastrophic outcome (crop failure)

- neglect of required action (failure to comply)

- lack of success (business failure)

- death of a dream (a failed marriage)

- predictable defeat (doomed to fail)

The late legendary Nobel prize-winning pioneer cardiologist Dr. Bernard Lown had a lot to say to his colleagues who use what he calls “words that hurt“. He once described this cardiac condition like so:

“Heart failure is not a disease. It’s just a description of clinical syndromes. A heart failure prognosis is no longer what it used to be; much of the damage that occurs to the heart may be reversible and the symptoms controlled over decades.”

And the words heart failure don’t even accurately reflect the definition of this condition: essentially, that your heart is not pumping blood as well as it should.

Dr. Lown, author of the compelling book “The Lost Art of Healing“, also wrote that deliberately using alarmist language (specifically, heart failure) is what otherwise caring physicians believe might somehow convey a sense of urgency, thus hoping to motivate patients to comply with doctors’ orders.

But ironically, the very opposite often happens instead. Trust, reassurance and helping to educate the patient are what will help to form meaningful partnerships. But instilling anxiety is bad doctoring, and threatens to intensify the severe emotional distress that so often accompanies a serious new diagnosis.

I once quoted Dr. Lown’s warning to his colleagues:

“ The doctor is part of our culture wherein doom forecasting is within the social marrow. Even the daily weather is often reported with anxiety-provoking rhetoric.

“To be heard, one learns the need to be strident, equally true for weather predictions as for medical prognostications. The end result is that doctors justify their ill-doing by their well-meaning.”

Here’s a disturbing example of how Canada’s Heart and Stroke Foundation chose to portray heart failure: a man slumped on a park bench apparently just waiting to die – as featured in their 2016 report called The Burden of Heart Failure.

In this grimly grey illustration (just one of several similarly distressing images chosen for this report), the Heart and Stroke Foundation matches a scary name with an equally scary image, which made me wonder:

“What on earth were these people thinking?”

The H&SF usually gets it right, in my opinion, but this particular national “awareness” campaign felt inexcusably hurtful to patients living with this diagnosis.

After eight full pages, the report does concede that “people can learn to live active, healthy lives” – even with a heart failure diagnosis. But why wasn’t that important message featured on page 1? And unfortunately, only one paragraph in the entire 12-page report even mentions depression.

Why this under-reporting of depression? As described by the European Society of Cardiology, new-onset depression occurs in over 40 per cent of patients within the first year after a heart failure diagnosis, and is associated with:

- loss of motivation

- loss of interest in everyday activities

- lower quality of life

- sleep disturbance

- change in appetite with corresponding weight change

- a FIVE-FOLD HIGHER MORTALITY RISK, independent of the severity of the diagnosis

And no wonder these people are depressed! They have just been told their hearts are failing.

This depression-associated reality is important because we know that heart patients suffering from such symptoms are far less likely to take their prescribed meds, exercise, improve their diet, show up for medical appointments and cardiac rehabilitation classes, quit smoking, lose weight, or be able to manage their considerable chronic stress.

Ironically, that list of instructions is precisely what the same physician who first drops the diagnostic “heart failure” bomb upon them will be recommending in the very next breath.

No matter how often alternative names are suggested, I’ve observed that the lukewarm response from both professionals and organizations so far reflects a solid lack of interest in a wholesale name change.

Instead, some in cardiology have started to take initial steps to simply distract heart patients from the F-word.

The American College of Cardiology, for example, now produces patient information material that is deliberately more positive than frightening (i.e. no old-dying-guy-slumped-on-a-bench images). Their excellent “CardioSmart“ website produces eye-catching posters, infographics and heart patient info (and they’ll even ship hard copies free to a clinic waiting room bulletin board near you).

The American Heart Association has also tried a more positive awareness campaign with the help of active and photogenic twin sisters Shaun Rivers and Kim Ketter, both nurses from Richmond, Virginia who now volunteer as AHA Patient Ambassadors. The sisters were each diagnosed with heart failure during the same week in 2009 when they were just 40. As Kim says: “We’re here to encourage and educate others!”

But in fact, both the ACC and AHA campaigns are handicapped from the get-go by the very words “heart failure”, delivered to new patients still reeling from that diagnostic gut punch.

For example, here’s how CardioSmart’s brand new “Learning to Live with Heart Failure“ patient video textbox starts off:

” If you just found out you have heart failure, you may feel scared or overwhelmed. And that’s okay.”

Except that this is NOT okay.

The reason you feel scared and overwhelmed is that some doctor has just told you that your heart is FAILING.

No matter how they try to dress up that devastating message with as much positive spin as they can muster, it’s still like putting lipstick on a pig.

Cardiologist Dr. David Brown told me via Twitter that he often raises his fingers to demonstrate air quotes around the words “heart failure” to more gently communicate to his patients that he doesn’t really mean “failure”.

But what other medical diagnosis requires clinicians to wiggle two fingers on each hand as air quotes?

This of course begs the question: do physicians cling to the name “heart failure” simply because that’s what they’ve always called it?

Like so many other scenarios in the practice of medicine, however, the treatment of this condition has profoundly changed over time. So why can’t we change its name, too?

Consider for example that what doctors insist on calling heart failure has a very long history, as outlined in the British Medical Journal (BMJ):

“Descriptions of heart failure exist from ancient Rome, Egypt, Greece and India, but little understanding of the nature of the condition existed until William Harvey first described the circulation in the year 1628. Meanwhile, treatment for centuries included blood letting and leeches.”(1)

Doctors abandoned the blood-letting and the leeches long ago with less resistance than currently exists to finally abandoning its name.

Personally, I don’t care what this diagnosis is called as long as you stop labeling it as a FAILURE.

Dr. Lown’s alternative name suggestion:

“Perhaps a better term would be stiff muscle syndrome.”

Dr. Brown offered this thoughtful option:

“The key concept is congestion to explain the symptoms of breathlessness and edema (swelling). Maybe congestive heart dysfunction?”

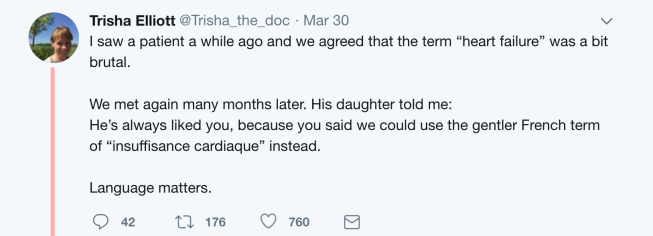

Scottish physician Dr. Trisha Elliott Cantley of Edinburgh has her own favourite substitute term: “insuffisance cardiaque”, as she suggested on Twitter:

Cardiologist Dr. Lynne Warner Stevenson, a professor of medicine at Harvard University, flat out declares: “We have to call it something else!” She prefers names like cardiac insufficiency, heart dysfunction, and – her favourite – cardiomyopathy:

” The term ‘heart failure’ denotes a hopeless defeat that may limit our ability to encourage patients to live their lives. Words are hugely powerful. Patients do not want to think of themselves as having heart failure. It can make them delay getting care, and it makes them ignore the diagnosis. I worry about that a lot. I also worry that patients don’t provide the support to each other that they could. Patients tend to hide that they have heart failure. We need to come up with a term that does not make patients ashamed.”

Whatever the diagnosis of heart failure is called in the future, using its current cruel name must be stopped. We need a systemic physician-led movement to stop using catastrophic language that clearly contributes to despair.

Please make it stop soon.

♥

1. Davis, R. C., Hobbs, F. D., & Lip, G. Y. (2000). “ABC of Heart Failure. History and Epidemiology.” BMJ Clinical research ed. 320 (7226), 39–42.

GOOD NEWS DEPARTMENT, December 2023: The British Medical Journal has published my Editorial called “Heart Failure: It’s Time To Finally Change the F-word“ in BMJ Open Heart. This project began as a lowly heart patient’s opinion piece, but ended up as an Editorial (in my experience, it’s very rare – almost unheard of! – to invite a patient to write an Editorial in a medical journal). Thank you to the brave BMJ Open Heart editors, reviewers and very helpful staff for making this publishing milestone possible! ♥

.

Q: What will it take to get the medical profession to correct the name of this diagnosis?

.

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote much more about adjusting to a new cardiac diagnosis in my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease”. You can ask for it at your local bookshop, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon, or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

See also:

CardioSmart’s information on Learning to Live With Heart Failure

Is it finally time to change the name ‘heart FAILURE’?

When doctors use words that hurt

Why aren’t more doctors like Dr. Bernard Lown?

Two ways to portray heart failure. One of them works.

When are cardiologists going to start talking about depression?

When grief morphs into depression: Five tips for coping with heart disease

Which one’s right? Eight ways that patients and families can view heart disease

Six personality coping patterns that influence how you handle heart disease

Why don’t patients take their meds as prescribed?

Non-inspirational advice for heart patients

.

Dear Carolyn

I hope you don’t mind but I put an extract from this week’s post on Health Unlocked, the British Heart Foundation forum.

People have been very positive and one person tells me she has ordered your book. Here is the link so you can see what has been written by grateful heart failure patients.

It touched a nerve for them. Thank you for your weekly posts – it makes me feel less isolated.

Best wishes.

Lindsay

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for letting me know, Lindsay! I’m glad that so many on your UK heart forum are also onboard; the patient comments in response to your posting were so interesting. I wish all cardiologists would read them and begin to understand how insisting on using the words “heart FAILURE” can actually hurt their patients.

LikeLike

What ticks me off is all the publications, at least in the US, showing happy, healthy people – usually white males who look very well off – doing all kinds of expensive activities, like piloting a power boat on the brochure for the heart failure clinic I go to. The message is, as I perceive it, that a) if you have money and b) if you’re male then c) you’ll live to a ripe old age free of symptoms of any disease whatsoever.

The other side of all this is not being told that any illness, even something quite minor, can destabilize well-compensated heart failure in, pardon the old pun, a heartbeat, and put you back at death’s door, struggling to breathe, on new meds that don’t seem to do any good, and making depression even more severe – and not being allowed to start a new antidepressant because it has a possible side effect of weight gain, even though I told her I have major depressive disorder. I mean, seriously?)

Yes, it happened to me. I’ve only slipped to class 2, but I resent that no one told me that a mere cough (turned out to be a very mild case of pneumonia, but I had no idea) could do this to me. And I am also angry that I’m being treated in a rote way by the heart failure clinic nurses, with no appreciation of me as an individual, let alone that the doctor wrote I “remain a complex and challenging case”, continued forward from when I was his patient in 2015. I’ve had numerous negative reactions to the new meds, and I’m not responding well to maxed-out doses of loop diuretics, but somehow they just can’t think outside the box with me.

And all this in spite of reporting increasing episodes of chest pain (doncha know that’s just acid reflux?) and chest pressure and fatigue and muscle weakness for the previous two years…

Sorry for the whine. I’ve been struggling with this since 2014, and what ground I gained in spite of horrible side effects to meds has been lost, probably forever. Yes, with all my health issues, I am a complex and challenging case. All the more reason to treat me as a unique individual…

Oh, wait, that’s how we should ALL be treated, regardless of color, gender, age, or any other characteristic!

Holly

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Holly. Those “healthy white males piloting a powerboat” brochure images are more examples of the bandwagon that other cardiology organizations seem to be climbing onboard – instead of addressing the inaccurate name of this condition in the first place, let’s try just putting a super-positive spin (or boat ride!) onto it. (Just imagine, Holly, if you do this heart failure thing correctly, you too would not only be perfectly healthy, but you’d be rich enough to buy a boat! IF you were a man, that is…)

You are indeed a complex and challenging case, but even calling you a “case” serves to distance the actual real person Holly from those clinic nurses. Instead of being seen as the individual you are (an individual with lots of lived experience AND some serious side effects to your meds), you’re being treated in a “rote way” by clinic nurses. This reminds me of the classic definition of what makes a “good patient”:

– get sick

– get treated

– get better

– thank your brilliant doctor!

You’re so right – EVERY patient, no matter who (and especially if they sometimes don’t fit that “good” patient stereotype) needs to be seen and heard as an individual with unique health issues. I’m sorry you’ve been struggling for such a long time; I hope you do find that care and respect you deserve. ♥

LikeLike

It caught my attention when Holly mentioned the “rote” nature of how she was treated.

Back when I started Nursing School in 1968, we were taught to remember that both Nursing and Medicine are a combination of “art and science” and the reason it is called Nursing Practice and Medical Practice is because we must be continuously learning and practicing our new learnings.

Over the years I have seen these ideas erode in the practice of medicine … science is the emphasis and personal pride in the ability to heal a disease is rampant. Our bodies are equipped with the most sophisticated self-healing systems that science has barely touched. No matter what medicine or surgery is applied to a dis-ease situation, it’s almost an adjunct to the systems of healing already in place….

I love a good physiology lesson but after studying mind-body and vibrational medicine for over 25 years I am amazed at how much medicine doesn’t know about the human body and how very little the practice of medicine has changed.

Treating people like individuals is an Art that needs to be practiced more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love that “art and science” lesson! Pride in the ability to heal IS important, yet you’re so right about some of the self-healing properties of the human body. In cardiology, we only have to look at the remarkable phenomenon of collateral arteries (those tiny’back-up” blood vessels feeding the heart muscle that can somehow, magically, go from zero to 60 when blood flow to that muscle is suddenly interrupted. “Do-it-yourself bypass”, as my cardiologist calls it!

LikeLike

I actually thought the man on the bench was taking a nap LOL.

I have spent many a post on the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy help site explaining that Heart Failure does not mean total failure of the heart.

I usually tell people that the term “heart failure” means the heart is not meeting the needs of the body as well as it should, and that it is easily treated with medications but does require close follow up.

It’s strange that diastolic dysfunction is used fairly often but I never hear systolic dysfunction. I think an official body will have to take a stance and I’m not sure when that will happen … for example “they” just recently coined the description “Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction” to describe Diastolic Heart Failure as opposed to Systolic Heart Failure🙄.

I have Diastolic Dysfunction …. and would definitely not like it called Stiff Muscle Syndrome as there is a very serious disease called Stiff Man Syndrome that it could get confused with.

Someone helped get “Broken Heart Syndrome” changed to Stress Cardiomyopathy …. I went for years with the stigma of “ broken heart syndrome” and people thinking that toxic emotions caused my heart to blow up, when it was asthma and the drug Albuterol that caused my episode of Stress Cardiomyopathy. So changes can happen.

If you get Canada to find a better name, I’ll help you work on America.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe the man on the bench was taking a nap while he was waiting to die!

I think you are absolutely right, Jill – an official body, a cardiology society, a cardiac organization will have to take the bull by the horns to change the name of heart FAILURE. “Broken Heart Syndrome” is indeed an example of a diagnostic name change (although media are often still fond of using the old “broken heart” descriptor because it’s so dramatic…)

Every single online reference I’ve ever found on heart failure is careful to explain upfront (like this one from Cleveland Clinic ) “It does not mean the heart has FAILED….”)

This is maddening! If it doesn’t mean that, why is this horrid word “failure” still being used?!?

I’ve been reading a lot lately about Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF). A note here for readers: Ejection Fraction (EF) simply measures the amount of blood that your heart is able to pump out of the left ventricle with each heartbeat; a ‘normal’ rate is about 50-60%.

Apparently half of all heart failure patients have this type of HF, but women are twice as likely to develop it.

LikeLike

What do you think of the following diagnosis, after a massive heart attack (due to complete blockage of the LAD) and placement of a stent? “Mild left ventricular cardiomyopathy” was the verdict, when I asked – I found the “mild” part of the diagnosis encouraging, although I had no idea at that point what “cardiomyopathy” was.

I am now almost 7 years out from the attack, on medications, of course, eating sensibly and walking briskly 6 days a week for 35-40 minutes. And a very low Ejection Fraction just after the attack has gradually improved to near normal, e.g. 50.

I do get tired if I overdo things – naps are my new best friend – and a little out of breath, if I walk too quickly. Otherwise, I feel pretty fit. Indeed, my current complaints mostly revolve around the increasing effects of osteoarthritis, as I age, i.e. joint stiffness and a sore back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this, Judy. What do I think of your “Mild left ventricular cardiomyopathy” diagnosis? I think it’s a perfect example of how people who have never been to med school interpret medical gobbledygook! One of my favourite examples is this interaction on the HealthTap website between a cardiac surgeon and a patient who asks: “Why did my arm hurt during my recent heart attack?” The surgeon’s response:

“The pericardium is innervated by C3,4,5 (Phrenic nerve). There may be some neuronal connections to the intercostobrachial nerves.”

This is how he talks TO A PATIENT!

In your case, no wonder you clung to that word “mild” – because that word was a bit of comfort compared to all the other jargon you were hearing.

Congrats on increasing that EF to 50. When you start noticing stiff joints more than cardiac symptoms, you know your heart is doing pretty darned well!

LikeLike

This post really hit home for me. I can clearly remember the first time those words were said to me. It felt just like a slap in the face. It was honestly worse than hearing the words “heart attack”. It made me feel like I was a failure along with my heart.

It’s not just doctors that need to choose not to use those ugly words. The entire staff in the cardiac care unit should get on board as well – nurses, patient education personnel, everyone. The attitude needs to be one of positive, helpful reinforcement. The word failure is not positive and it is not helpful.

(Don’t even get me started about some of the scare tactics used to “encourage” patient compliance. I had one nurse tell me that eating one sodium rich meal could be fatal.)

Thank you so much for this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Inge, you raise so many important points – especially the need for ALL medical staff to get onboard, not just the docs. No staff should ever be making patients “feel like a failure”. I doubt if this is deliberate cruelty. It’s more likely just being thoughtless, and no longer caring what hurtful effect one’s words will have on this frightened human being in front of them.

This does require a conscious shift in attitude, better training, and strong leadership from the top down. Changing the name could be the first step of many.

LikeLike

Once again, I applaud you Carolyn. What an incredible piece you wrote. Everything you said was true and I experienced my diagnosis in the same way.

I was paralyzed the first year after my diagnosis and had deep depression. It’s a devastating definition currently used. The surgeon who put in my stents and delivered my diagnosis was cold and flat. I’m sure he says it about 10 times a day every day, but with no understanding on how incredibly emotional it is for the patient. “You have Heart Disease.” “You have Heart Failure.”

Here was my diagnosis: “You have heart disease. You had 2 blocked arteries and we put in 2 stents. The rest of your arteries don’t look good either.”

May I suggest simply explaining what was wrong? “We found two blockages and we fixed them with two stents. We recommend you attend a heart education program to find out how you can live a healthy and fulfilling life. Your cardiologist will work with you to ensure that your heart remains strong.”

Keep up the great work!

Kelly

(Toronto, Ontario)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Kelly and thanks so much for your kind words. I had to make a face when I read what that doctor told you: “The rest of your arteries don’t look good either…” What on earth is any patient hearing those words, in the middle of such an overwhelming and scary experience, supposed to do with that statement?

Your suggested alternative seems much kinder, and would take only a few seconds longer to say than it does to be cruel and thoughtless. We don’t need sugar-coating. We need the truth, delivered with common courtesy.

LikeLike