by Carolyn Thomas ♥ @HeartSisters

Emergency physician Dr. Pat Croskerry tells the story of the day he misdiagnosed a patient who was experiencing unstable angina – chest pain caused by coronary artery disease, and often a warning sign of oncoming heart attack. But this is what he’d said before sending that patient home:

“I’m not at all worried about your chest pain. You probably overexerted yourself and strained a muscle. My suspicion that this is coming from your heart is about zero.”

In a later interview with Dr. Jerome Groopman (author of a book I love called How Doctors Think), Dr. Croskerry explained how easily that misdiagnosis happened:

“I missed it because my thinking was overly influenced by how healthy this patient looked, and by the absence of cardiac risk factors.”

“The patient’s unstable angina didn’t show on the EKG, because 50 per cent of such cases don’t. The unstable angina didn’t show up on the cardiac enzyme blood test, because there had been no damage to the heart muscle yet. And it didn’t show up on the chest X-ray, because the heart had not yet begun to fail, so there was no fluid backed up in the lungs.”

Dr. Croskerry was shocked when he learned the next day that his patient had returned to Emergency – but this time correctly diagnosed and treated for a heart attack. He realized that he had confidently made a diagnostic error that could have resulted in the patient’s death (but luckily, did not).

When he was a medical student, he recalls that very little attention was paid to teaching what he now calls the “cognitive dimension” of clinical decision-making – the process by which doctors interpret their patients’ symptoms and weigh test results in order to arrive at a diagnosis and a treatment plan.

He added that his instructors back then rarely described the mental logic they relied on to avoid mistakes like his. He added:

“When people are confronted with uncertainty – the situation of every doctor attempting to diagnose a patient – they are susceptible to unconscious emotions and personal biases, and are more likely to make cognitive errors.”

Now, as a professor of Emergency Medicine at Dalhousie University Medical School in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Dr. Croskerry is a trailblazer in teaching med students the skills of critical thinking. He implemented at Dal the first undergraduate course in Canada teaching students about medical error in clinical decision-making, specifically around why and how physicians make diagnostic errors.

Learning to improve critical thinking skills often requires relearning the many factors that can influence how the human brain helps us make decisions.

One important working model of decision-making is what Dr. Croskerry calls the Dual Process Theory. This broadly divides the brain’s ability to make decisions into intuitive (System 1) or analytical (System 2) thinking. System 1 thinking is intuitive, automatic, fast, frugal and effortless, and especially dependent on context.

Most decision errors occur in System 1 thinking.

Dr. Croskerry wrote more about this in his Healthcare Quarterly journal essay called “Context is Everything, Or How Could I Have Been That Stupid?“

Context:

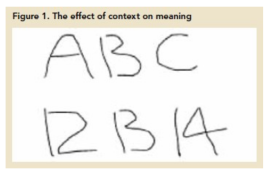

One of the major constraints on System 1 decision-making is context. Here’s an example from Dr. Croskerry:

The middle figure on the top line clearly looks like the letter B. The middle figure on the bottom line looks like the number 13. But the two figures are, of course, exactly the same.

It’s this context that can affect our interpretation of what we see, and can also confuse meaning.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio:

Dr. Croskerry explains that when making decisions, we also need to be able to distinguish important signals from background noise. But signals rarely arrive all by themselves. They’re usually accompanied by some type of noise or interference.

“A particular problem for physicians is the degree of overlap among diseases. Some (e.g., shingles or shoulder dislocation) usually present little challenge for diagnosis because they are relatively readily identified. They are accompanied by very little ‘noise’.

“But other diseases (e.g., pericarditis or acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) manifest themselves less clearly and may be mimicked by other conditions. The probability of diagnosing the disease on the basis of clinical presentation alone may be no better than chance because ‘noise’ may completely overlap the signal.”

“The decision-making of clinicians may be influenced by distracting cues (noise) from the patient in front of them.

“Physicians can also be influenced by factors that may be irrelevant to the provision of appropriate care, such as gender.”

Regular readers will already know about current cardiac research on implicit bias, also known as the cardiology gender gap. As I’ve written about (here, here, here, and here, for starters), we know that women are significantly more likely to be both under-diagnosed during a cardiac event, and then under-treated even when appropriately diagnosed compared to our male counterparts. See also: Skin in the Game: Taking Women’s Cardiac Misdiagnosis Seriously

When the Emergency physician misdiagnosed my own “signal” (textbook heart attack symptoms), for example, one of his first confident pronouncements to me (based on the “noise” in front of him, i.e. I was a middle-aged woman) was:

“You are in the right demographic for acid reflux.”

But decision errors, of course, don’t happen only in cardiology.

Dr. Croskerry adds that the decisions of healthcare professionals may also be be influenced by the background “noise” of other irrelevant factors such as the patient’s race, weight, mental illness or age.

When teaching his medical students how to minimize this type of noisy interpretation, Dr. Croskerry often starts off with a quiz to test their current critical thinking skills (based on a Cognitive Response Test, Frederick 2005).

For example, the first quiz question is:

“A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

The majority of answers given by his students are wrong. The usual answer is that the bat costs $1 and the ball costs 10¢. This fast, intuitive response is incorrect – because the bat would then cost only 90¢ more than the ball. (The correct answer is that the ball costs $.05 and the bat costs $1.05).

If you too guessed the wrong answer, it’s likely because your brain was engaging in a System 1 critical thinking error.

So what can patients do if they believe it’s time to rethink a physician’s diagnosis?

Dr. Jerome Groopman recommends that you ask these questions of your doctor:

- “What else could it be?” The cognitive mistakes that account for most misdiagnoses are not recognized by physicians; they largely reside below the level of conscious thinking. When you ask simply: “What else could it be?”, you help bring closer to the surface the reality of uncertainty in medicine.

- “Is there anything that doesn’t fit?” This follow-up should further prompt the physician to pause and let his/her mind roam more broadly.

- “Is it possible I have more than one problem?” Posing this question is another safeguard against one of the most common cognitive traps that all physicians fall into: search satisfaction. It should trigger the doctor to cast a wider net, to begin asking questions that have not yet been posed, to order more tests that might not have seemed necessary based on initial impressions.

.

1. K. Hamberg. “Gender Bias in Medicine.” Women’s Health, (May 2008), 237–43.

♥

Q: Have you ever made important decisions that turned out to be based on context or ‘signal-to-noise’ thinking errors?

See also:

Misdiagnosis: is it what doctors think, or HOW they think?

Misdiagnosis: the perils of “unwarranted certainty”

The science of safety – and your local hospital

Mandatory reporting of diagnostic errors: “Not the right time?”

Misdiagnosed: women’s coronary microvascular and spasm pain

The shock – and ironic relief – of hearing a serious diagnosis

Why hearing the diagnosis can hurt worse than the heart attack

I’ve just been to hospital with an increased heart rate, palpitations and chest pain, I had an abnormal ekg with inverted T waves, but was told that I have anxiety and this was causing the increased heart rate and it was up to me whether I stay in hospital or not. I decided to come home, as I had been there for eight hours with nothing to drink except 1 small cup of water, they did say I need to see a cardiologist though, but I’ve had SVT for 3 years and my cardiologist didn’t tell me until this year, as my GP put me on bisoprolol because my heart rate was too high. The ENTs gave me the trace they did though, so I will show this to cardiologist.

LikeLike

Excellent column. I agree re reader’s comment about contextual thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

I so appreciate you and your resource. We need to be advocating for ourselves 24/7.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So true, Roslyn – we all do need to be our own best advocates!

LikeLike

Just a comment in general. I object to the name given to system 1 as “Intuitive Thinking” and instead prefer something like “contextual thinking”. This is important and here is why.

True intuition is that still small voice that speaks to us from a consciousness much higher than the right brain or the left brain. For way too long, doctors and others have been trained out of using true intuition.

I’m not saying to throw out critical thinking… it is imperative. But even after the facts are in and the critical thinking model applied, I’d like my doctor to take a deep breath, close his eyes and feel good intuitively about the decision he is making or the advice he is giving.

I have seen doctors go against all critical thinking because something doesn’t feel right and have saved lives because of it. Maybe one day they can add Centering in, Quieting the brain and Hearing your inner voice in Med school.😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jill – I think you’d really enjoy watching Dr. Croskerry in action while speaking on patient safety and diagnostic errors at Emergency London Grand Rounds – here’s the link to this video (about an hour, but SO interesting!) This helps to understand why most medical misdiagnoses actually occur during that gut feeling intuition stage of Systems 1 thinking!

LikeLike

Very interesting article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Carolyn!

LikeLike

I was ignored during a botched endometrial ablation. Uterus badly burnt. She also burnt into my small bowel. 5.5 months of agony, I lost 90 pounds. Nearly died of sepsis or bullet to the head.

It was so bad after being ignored over and over again. Shunned bullied screamed at by MDs that I was wasting hospital time and resources. I even had a forced psych evaluation. I wasn’t depressed until I was forced the psych evaluation. I wasn’t suicidal until after it. If the last MD more than 10 hours away didn’t take me seriously I was ending my life.

19 ER visits. Couldn’t keep down a bottle of Ensure meal replacement a day. When the surgeon opened me up organs were rotting. Oh yes. I got nothing for pain. Not a freakin’ thing in all this.

I was labelled an addict but blood urine and hair follicles tested clean. I already hated MDs because in 2001 I was supposed to be out cold but I wasn’t. I was sexually assaulted by an MD. Now getting anything done is a disaster. I have medically induced PTSD.

I put in complaints for them to be ignored. Now I have a lump in a breast. I’ve known for 18 months, do I care to get it imaged, screw that. The hysterical woman. Yeah right. Medical bias absolutely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re describing every patient’s worst nightmare, Christine. I’m so sorry that all of this has happened to you, and am not surprised at all that you hate the thought of facing another medical specialist or procedure ever again after what you have been through. No wonder…

I’m not a physician, so I can’t comment on your decision to ignore that breast lump. It’s scary to imagine that you’re choosing to do so, but nobody can possibly judge your decisions, given your traumatic past experience. Good luck to you…

LikeLike

Christine, your situation is horrid. As a nurse and a member of the health care professions I am appalled.

For what it’s worth. I have found the women involved in Breast Cancer screening movement extremely compassionate. Call a Breast Cancer Support Group, find some one to help you navigate the system and go with you to your appt. as an advocate.

My best friend ignored her breast lump and now has bone metastasis and needs painful chemo therapy. I pray your lump is benign and that you find the support you need to go through an evaluation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Part of the problem is getting around the Cardiologist’s ego. And paternalism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Sandra – that IS part of the problem. Even some cardiologists suggest this to be true.

For example, Dr. Michael Chester, consultant cardiologist and director of the National Refractory Angina Centre in Liverpool, England, wrote in the British Medical Journal (BMJ):

“Great harms are done inadvertently to patients by benign paternalists who genuinely believe that their decisions are more important than their patients.”

Ego seems to me to be an occupational hazard among medical specialists: we are referred to them because of their superior knowledge and experience, we trust that they will be superior in their knowledge and experience, and then we are surprised by their belief in their own superiority.

LikeLike