by Carolyn Thomas ♥ @HeartSisters

A cardiologist who teaches medical students at a prominent medical school was asked if his students were learning about the known disparities in cardiac research, diagnostics, treatment and outcomes in female heart patients compared to our male counterparts. His answer basically was: “If we start taking up time to talk about women, we’d have to stop teaching one of the equally important subjects in our curriculum.” See also: Women’s Heart Health: Why it’s NOT a Zero Sum Game

That reluctant conversation-stopper may help to explain what cardiac researchers keep reminding us: physicians now in practice likely received little if any specific med school training in women’s health aside from reproductive health issues. And as Emergency physician Dr. Alyson McGregor at Brown University reminds her colleagues:

“Women are NOT just men with boobs and tubes.”

In her compelling book, Sex Matters: How Male-Centric Medicine Endangers Women’s Health and What We Can Do About It , Dr. McGregor adds:

“We have our own anatomy and physiology that deserves to be studied. One of the biggest and most flawed assumptions in medicine is: if it makes sense in a male body, it must make sense in a female one, too. But in every aspect, our current medical model is based on, tailored to, and evaluated according to male models and standards.”

Australian researcher Dr. Lea Merone is on the same page, explaining that the current male medical model is “androcentric” – from the Latin ‘andro’ (man, male) and ‘centric’ (centred on). What this means, she adds, is “a tendency to place the male or masculine viewpoint and experience at the centre of a society or culture.”(1) As she wrote last year in the medical journal Women’s Health Reports:

“The androcentric history of medicine and medical research has led to an ongoing sex and gender gap in both health research and education. Evidence suggests that globally, this sex and gender gap is ongoing. These gaps translate into real-life health inequities for women.”

For example, most medical research has been performed on (white, middle-aged) males for decades – and then generalized after the fact to apply to female bodies, as if researchers believe that women are just small men. Even the laboratory animals used in medical research have traditionally been male animals.

This unbalanced research gap, as Dr. Merone suggests, also translates into a medical education gap in which, “outside of reproductive and sexual health, both medical/nursing schools and clinical textbooks sometimes omit women entirely.”

Here’s a frightening example: the results of a survey called Sex- and Gender-Based Medicine Faculty Survey, as described by Mayo Clinic’s Dr. Virginia Miller, and administered to 159 medical schools in Canada and the US, revealed that 70% of respondents reported receiving no formal sex- and/or gender-based curriculum content during their training.(2)

Dr. Miller also reminds us, by the way, that the words “sex” and “gender” are two different things: sex is narrowly defined as a person’s reproductive organs at birth, and gender is more widely defined as a person’s identity, expressions, and role in society.

Meanwhile, medical school training has focused on what’s called the ‘bikini approach’ to women’s health – in which women’s health focuses heavily on breasts and reproductive systems, i.e. the parts of a female body typically covered by a bikini. And we know that sex- and gender-specific educational content about cardiovascular disease diagnosis and management is sorely lacking in most med schools.

This summer, I’ve been invited to speak about women’s heart disease to students – first to nursing school students in Vancouver, and most recently to med students in New York. After the American Heart Association’s last national survey results revealed a shocking public awareness campaign failure that the AHA itself dubbed “a decade of lost ground” , I now believe that reaching out to educate young medical and nursing trainees could be a better option to improving our future as female heart patients.

There may be a light at the end of this androcentric tunnel – and it has already begun – with medical/nursing school training. In the U.K., for example, starting in 2024, specific teaching and assessments on women’s health will become mandatory for all graduating medical students (and for all incoming doctors) as part of its first Women’s Health Strategy for England.(3)

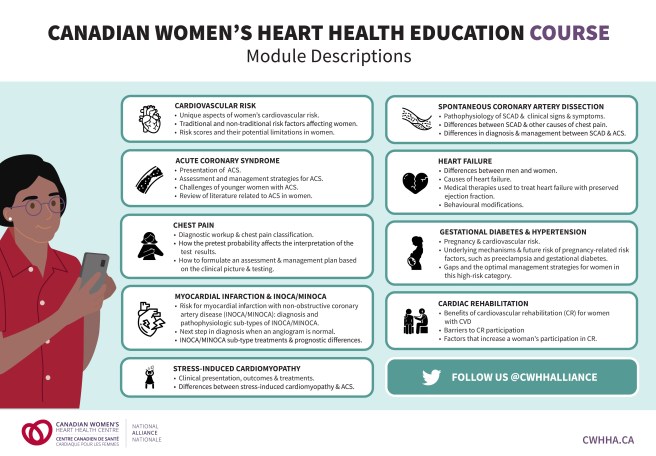

Meanwhile, the Training and Education Working Group of the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance (CWHHA, affiliated with the University of Ottawa Heart Institute) has designed nine educational modules on women’s cardiovascular disease. These modules target medical/nursing trainees, as well as current healthcare professionals in Cardiology, General Internal Medicine, and Emergency Medicine. Each free pre-recorded webinar ranges from 24-37 minutes in length, and includes a downloadable Power Point slide deck with speaking notes, a full reference list linking to the articles, and a heart patient sharing her lived experience via YouTube video.

Together the nine modules offer a one-stop Master Class package to any academic tasked with teaching future doctors and nurses about women’s heart health. These include:

- Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Women – The Role of Risk Factors and Scores: This module explains limitations of current cardiac risk calculator scores doctors use (none of which include pregnancy complications, a risk factor unique to women which can double our risk of heart disease. That’s as serious a risk factor in women as smoking and high cholesterol, yet how many docs even ask women about their history of such complications?)

- Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) in Women: This topic covers assessment and strategies for managing this sudden, reduced blood flow to the heart muscle (as in heart attack or unstable angina) and also reviews additional challenges presented by younger women with ACS.

- Approaches to Chest Pain – A Sex & Gender Focus: (the most commonly reported cardiac symptom in both women and men – even though women might not use the word “pain” to describe chest symptoms (e.g. pressure, fullness, dull ache, etc.) which does NOT mean symptoms aren’t heart-related. This module reviews an appropriate diagnostic workup for women with symptoms.

- Myocardial Infarction (MI) with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): Myocardial infarction (MI) means heart attack that’s typically caused by an obstructed coronary artery – compared with MINOCA (Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries) – both more commonly seen in women. This module helps to identify the next step in diagnosis when the angiogram appears “normal” and describes how treatment differs between the sub-types of MINOCA/INOCA.

- Stress-Induced Cardiomyopathy (SIC): Cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart muscle that makes it harder for the heart to pump blood through the rest of the body. This module addresses the clinical presentation and associated triggers for SIC, and revisits the differences between treating SIC and acute coronary syndrome.

- Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD): The majority of SCAD patients are young women (average age 45-53 ) with few if any cardiac risk factors; this module explains the important differences between SCAD and other causes of chest pain, and what emerging research concludes about best practices in treating SCAD.

- Contemporary Management of Women with Heart Failure: This module examines the difference between men’s and women’s heart failure diagnoses, and especially the medical therapies used to treat heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF – which is most often seen in women) and also why sex-specific risk factors like early menopause or adverse pregnancy outcomes can help predict which women are more likely to have this diagnosis.

- Cardiovascular Risk In Women With Gestational Diabetes & Hypertensive Disorders Of Pregnancy: This module reviews the gaps and optimal management strategies for these women, and the underlying mechanisms and link between pregnancy-related cardiac risk factors and heart disease.

- Recovery & Cardiac Rehabilitation: This module explains the remarkable benefits of cardiac rehab for all female heart patients, identifies barriers that deter women from participating, and influences (such as physician endorsement) that can increase women’s participation.

Stakeholders committed to improving professional health education on women and heart disease (like these nine modules) include students, faculty, deans, alumni, donors and advocates. It’s a big and optimistic tent!

♥ Learn more on how to access these nine free CWHHC educational modules.

Once you’re registered (registration is free in Canada or the U.S.) there are two potential ways to use these nine educational modules:

- if you’re interested in learning more about women’s cardiovascular health, you can view the webinar sessions

- if you’re part of a medical or nursing school faculty, you can download the tools (PowerPoint slides, speaker scripts and resources list) to present content at your own institutions (i.e. Grand Rounds) – and you can also contact CWHHC for invited talks

I must add here that featuring real heart patients talking about their own lived experience is a stroke of genius in each of the nine teaching modules. I’d like to acknowledge the nine women who brought these modules to life by sharing their unique perspectives: Monique, Kelly, Nicole, Bobbi Jo, Bev, Sudi, Marie, Christine and Charlotte.♥

And remember that surprising comment from the cardiologist I mentioned at the beginning of this post? I suspect that even he could somehow manage to schedule nine short educational modules during a med school term without threatening the rest of his curriculum content.

I’m already a wee bit giddy anticipating entire graduating classes of new physicians and nurses informed by these powerful modules in the nearest possible future.

♥

Q: Do you believe that reaching medical and nursing students might finally lead to improved cardiac care for women?

.

See also: “Incorporating a Women’s Cardiovascular Health Curriculum Into Medical Education“, published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

NOTE from CAROLYN: I wrote more about the disparity in women’s cardiac research, diagnostics, treatments and outcomes compared to men in Chapter 3 of my book, A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease. You can ask for it at your local library or bookshop, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon – or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

♥

Carolyn, your story is so eerily similar to mine. I was also sent home from the ER while experiencing classic heart attack symptoms. I was told, “100% nothing wrong with your heart”, and “go home and take Tylenol”.

Two days later, I had a major heart attack that I barely survived.

My family doctor, a woman, was very angry, and told me to tell my story to as many women as I can. She told me to tell these women to never leave the hospital until they are taken seriously.

Good for you!

LikeLike

Hello Lucille – the part of your own cardiac crisis that leaped out at me was that absolute certainty of Emergency staff in concluding that what was happening to you was NOT actually happening. My standard response to experiences like ours is to ask: would a man with our “classic heart attack symptoms” be so confidently dismissed and sent home from Emergency?

Your family doctor’s advice to keep telling other women your story is a breath of fresh air!

Hope you’re doing much better now. Take care. . .♥

LikeLike

Thanks for this post, Carolyn. I’m puzzled, though, as to why there is no mention of arrhythmias in the topic of women’s cardiovascular health.

I’ve had certain awful experiences in the 10 years I’ve lived with AFib that I can attribute to the very narrow masculine mindset of the electrophysiologist(EP) or cardiologist dismissing my concerns.

What I experienced most recently is simply abusive and makes no sense at all. I am so incredibly tired of this nonsense!! It’s not only costly in terms of the emotional, physical, and psychological impacts, but it makes no sense economically in a system that prioritizes money.

Fortunately, I made my way to a new EP who seems to actually listen and take my concerns seriously. 2 weeks ago I had my 5th ablation; this one was needed to address the intense flare up of episodes resulting from the intense stress of the latest wave of being dismissed and actually blamed for things that were not at all my fault. It is sheer insanity.

I’m also an HSP – ‘Highly Sensitive Person’ – which means I have the innate trait of sensory processing sensitivity. This is not a disability or diagnosed disorder, but rather a trait found in around 20% of the population, and means that my nervous system is wired to take in a lot more stimuli than most folks. I consider it a superpower.

The challenge in health care is that I’ve frequently been in stressful situations with devoid-of-empathy, dismissive health care workers which have quickly overstimulated my sensitive nervous system. A nightmare for anyone w/AFib, as this is what triggers episodes.

I mention this trait, which means that we’re included in the neurodiverse community, because I wouldn’t be surprised if other women out there with cardiovascular issues are also neurodiverse – and they may not realize it.

The stress of trying to navigate the rather insensitive wider culture as a sensitive person can build and result in health issues. But understanding the trait and transforming one’s lifestyle makes a huge difference. Anyone interested in looking into the trait should Google Dr. Elaine Aron and check out the self-diagnosis quiz on her site.

With the EP I was with for 4 years in that famous, stressful, dysfunctional hospital system I recently left, I explained the trait several times. Neither he nor his staff acknowledged a word I said. Stonewalled. What’s missing with the bone-headed, narrow-minded, masculine view of women’s cardio health is the importance of culture.

Anyone coming anywhere near a cardiac patient, especially a sensitive female, needs to be *gentle*(!!), kind, empathic, compassionate and really listen. People lacking these traits should not have those jobs. Period.

I imagine my case is a riff on the theme you’re writing about – we women tend to be pretty attuned to our bodies. When we express what’s going on and we’re not listened to or empathized with, we can predict what will go wrong. In my case, it did and the result was an intense worsening of the symptoms I was there to be treated for, which required yet another ablation.

Rather than a curious opening of the mind, what I eventually experienced was being dismissed. And blamed.

In one of the final conversations I had with that last EP, I said, “I’ve shared several times about my sensitivity, but I’ve never understood that you’ve believed me. I’m puzzled by this.”

His response: “It doesn’t matter if I believe you or not. All the care is tailored.”

OK. So the basis of truly tailoring my care is, again, dismissed. But my care is tailored?

I’m certain that I wouldn’t have needed so many ablations if I had truly been listened to. I’m one patient who’s completely fed up with the overly masculine mindset nonsense, as the stress of it has had a direct, negative, traumatizing, expensive, measurable impact on my health. Enough already!

Thanks for the great work you’re doing, Carolyn. 🙂

LikeLike

Hello Nella and thank you for such a thoughtful and intriguing comment. I can’t answer your question on why the University of Ottawa Heart Institute started these initial medical education modules focused on coronary artery disease and not arrhythmias (or congenital heart defects or valve problems or any other cardiac problem!)

I’m glad that you have finally found yourself a good EP who LISTENS to you! Many docs underestimate the profound relief this brings to women who are used to being dismissed or ignored or worse. What that dismissive approach inevitably causes is a profound sense of abandonment (“I’m sick, but now I’m not being heard, which is making it even worse!”) and also what researchers call “treatment-seeking delay behaviour“

Thanks for sharing your unique perspective on being a Highly Sensitive Person. I was first introduced to this in relation to medical diagnoses by Dr. Barbara Keddy at Dalhousie University in her book on fibromyalgia (she’s lived with FM for decades – and has also survived a heart attack). I have quoted her work many times over the years because I was so struck by how similar her FM patient experience was to my own heart patient experience. She wrote, for example about the relationship between sensitivity and empathy, and why are women more prone to developing FM than men are. She now believes that this chronic diagnosis tends to more frequently hit the “highly sensitive person” – who is also more likely to be misunderstood by healthcare providers. She says she was “aghast” when she read in a review article about FM that those with FM are “exhausting to manage”, “perfectionists” and “demanding” – and that they often have “personality disorders” like histrionic behaviors. Imagine how healthcare professionals who describe patients like this will treat the poor schmuck who shows up expecting professional help and common courtesy! Dr. Keddy calls articles like that in her latest book “not only useless but dangerous!“

My belief is that people in the neurodiverse community are showing up at medical appointments and Emergency Departments and walk-in clinics all day long with a broad range of serious health issues – including but certainly not limited to cardiac issues – that they desperately need help managing.

PS That doctor who told you it doesn’t matter if he believed you or not?! Clearly zero understanding of the meaning of the word “tailored”. OUCH!

Take care, thanks for your kind words. ♥

LikeLike

Thanks, Carolyn.

More to say, but my heart is signaling the need for a break from heart/health care talk. It needs that at times. 🙂

Best wishes to you.

LikeLike