by Carolyn Thomas ❤️ Heart Sisters (on Blue Sky)

As far back as I can remember, I have always been one of those annoyingly cheerful early morning people who bounce out of bed most mornings, raring to go. And so when I first heard the term “optimism bias”, my immediate reaction was:”That’s me!” But there’s apparently far more to optimism bias than bouncing cheerfully out of bed. (And my own mornings are admittedly less bouncy lately, given that I’m approaching Round 3 of chemotherapy for breast cancer, including a whack of side effects that have often felt like being run over by a large bus).

Dr. Neil Weinstein, a professor and researcher at Rutgers University, was among the first psychologists to study what he defined as “over–estimating the likelihood that good things will happen to us, and under–estimating the likelihood of bad things”. He labelled this: “unrealistic optimism”.

Dr. Weinstein’s work on optimism bias suggested that most people tend to under-estimate how susceptible to harm they are – including to a serious health crisis. Consider these other examples of unrealistic optimism:

- Most people believe that they are at far lower risk of being a crime victim than other people are.

- A National Cancer Institute study on college students found that those who were overly optimistic engaged in more binge drinking episodes.

- Smokers believe that they are less likely than other smokers to contract lung disease.

- America remains at 57th place in the world’s 2025 Climate Change Performance Index ranking, yet the Trump administration has eliminated climate programs and research.

- Research on compulsive gambling shows that these gamblers are overly optimistic about winning. (HOT TIP, gamblers: The HOUSE ALWAYS WINS!)

Dr. Weinstein’s research suggested that our future expectations may become biased because we tend not to expect problems we have not already experienced.

As a heart patient for the past 17 years, this makes perfect sense to me. I often say, for example, that heart disease did not matter to me until it happened to me. I was no more likely to worry about heart disease than I was about lupus or epilepsy or any other serious diagnosis that did not affect me or somebody I care about.

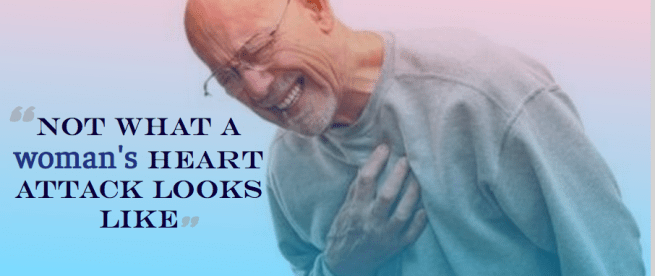

And like many women, if I ever gave a moment’s thought to heart disease (which was approximately NEVER), I would have pictured a man. I viewed this as a man’s problem.

And like many women, if I ever gave a moment’s thought to heart disease (which was approximately NEVER), I would have pictured a man. I viewed this as a man’s problem.

This unfortunate stereotype continues to inaccurately inform women who may believe that a “real” heart attack must always look like this – even when we are experiencing the more common slow onset heart attack – in which symptoms come and go, and come back again over time.

Women are known to default to unrealistic optimism when we try to minimize or ignore even the most severe cardiac symptoms instead of seeking urgent medical care. See also: “Six Reasons Women Delay Seeking Help During a Heart Attack”

I learned during those 17 years that the strongest predictor of a heart attack is having already had one. So until recently, I fully expected that “heart disease” would be listed one day as the cause of death in my obituary.

That is, until April 1st of this year – when I first heard the diagnosis “invasive ductal carcinoma” aimed out loud in my direction – the most common form of breast cancer in women. In simplest terms, I’ve come to believe by now that my cardiac treatments were designed to make us feel better. The treatments for breast cancer, however, generally make us feel far worse before we get that glimpse of “better”.

Breast cancer? BREAST CANCER!? Isn’t 17 years of living with heart disease ENOUGH? I can tell you that it’s tough to feel optimistic when you’re sick with crushing fatigue and other debilitating side effects of an aggressive treatment plan.

But optimism is what my family and I did feel when we learned that my malignant 9-centimetre tumor had already shrunk considerably – after just my first round of chemotherapy in June. That shocking reality immediately boosted our optimistic confidence, and also reduced the dread of chemotherapy – because we can now see clear evidence that these powerful drugs are working.

I’ve observed (and decades of research back this up) that unless we have an immediate family member diagnosed with a significant and/or inheritable condition, most women spend precious little time thinking they’re at risk of a medical crisis in the near or distant future – which helps to explain our profoundly shocked reactions to being diagnosed – almost as if we truly believe that bad things will happen only to other people, but never to us.

Most women are afraid of breast cancer, when what we should fear is heart disease, which actually kills six times more women each year than all forms of cancer combined. And if we were truly concerned about the most dangerous cancer in women, we would all be donating to lung cancer fundraising campaigns.

But underestimating our health risks may explain why we’re often so bad at healthy behaviour change – even when we find out we’re at higher risk of poor outcomes.(1)

Stéphanie Colle-Watillion studies brain health, and she describes a unique expectation in her own family history that may be familiar to many readers, too. She wrote:

“I always assumed that my mother would live well into her 90s as her own mother had done, and that my father, a heavy smoker, would pass in his sixties. Yet life surprised me. My mother died at 74, while my father, despite his very unhealthy lifestyle, lived to 82. But he was always the one who worried less, took life as it came, and maintained an unwaveringly optimistic outlook. It made me wonder, did his positive mindset contribute to all those extra years?”

Researchers found that when they studied people living with chronic illness, those who reported that they enjoyed life despite their day-to-day symptoms experienced a lower mortality risk compared to patients with comparable illness who did not report similar enjoyment. Those who generally had what personality researchers call a positive affect (e.g. joy, interest, alertness) also shared a lower mortality risk compared to patients with a negative affect (e.g. fear, distress, anger). (2)

In fact, a positive affect was particularly protective among those over the age of 65 – even when reporting higher levels of stress.(3)

Both unrealistic optimism and unrealistic pessimism are extremes on the same continuum, as Jane Collingwood explains at Psych Central.

“The midpoint is realism. Realists explain events just as they are. Realistic optimists are cautiously hopeful of favourable outcomes, but they do as much as they can to obtain desired results. The unrealistic optimists believe it will all turn out well in the end, yet may not do what is required to achieve that.”

.

1. Rozanski A et al. “Association of Optimism With Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality”. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Sep 4;2(9):e1912200.

2. Sharot, T. “The Optimism Bias.” Current Biology, 21(23), 2011. R941–R945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.030

3. Moskowitz, J. et al. “Positive Affect Uniquely Predicts Lower Mortality Risk. Health Psychology” 2008.

.

Q: Are you generally an optimist, a pessimist or a realist?

♥

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote much more about becoming a patient in my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease” (Johns Hopkins University Press). You can ask for it at your local library or bookshop. Please support your favourite independent neighbourhood booksellers, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon – or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

♥

P.S. Dear readers: Thank you for your supportive and kind messages in response to my recent breast cancer diagnosis. Updates here.

Your writing is such a powerful reminder of how complex optimism really is — it’s not just cheerfulness, but the way we make sense of uncertainty, illness, and the parts of life we never expected to face. The way you describe unrealistic optimism, especially in the context of women’s health, really hits home. So many of us assume “it won’t happen to me” until it does.

I’m deeply moved by your honesty about navigating both heart disease and now breast cancer. The contrast between feeling worse during treatment but more hopeful because the chemo is working… that’s real, grounded optimism. Not denial — just choosing to hold onto evidence that things can get better.

Thank you for sharing this. It’s a perspective many people need but rarely hear voiced so clearly.

LikeLike

Hello Zoha princess – thank you for your kind words. For me, feeling optimistic or hopeful because the chemo was working as planned – all while suffering predictably worsening pain and disability directly because of those toxic chemo drugs – is getting more difficult with each passing day. I can truly understand completely breast cancer patients who simply give up. For them – and perhaps one day for me, too – this is entirely a ‘quality-of-life’ issue in which the side effects of the treatment are so much worse than the cancer itself. I’m just finishing a new article (for this Sunday) that revisits Quality of Life vs. Length of Life. Thank you again. . .

Take care. . . ❤️

LikeLike

Yes, I agree with others who have commented on you, Carolyn and your courage and hope and optimism in the face of the cancer diagnosis on top of all of the others.

And I, too, send you healing thoughts and ask for you to experience healing and peace and joy. The question you ask is very interesting. My spouse, Umit, and I were talking about this very question just a few days ago, in relation to something else. I think that because I was a very late arrival (in the 1950’s when I was born) to my parents, with my parents being older, I did see them go through more health issues.

When I was 9 my mom turned fifty which led me to assume that her life was half over at that point. That in itself led me to ponder mortality for a period of time. But, in general, I tend to have a very hopeful approach to life. As one of your other readers remarked, I think I move between pessimism, optimism, and realism quite a bit.

I would characterize myself as more hopeful than optimistic. I have had quite a few health dramas and have been extraordinarily fortunate to have come through everything as well as I have. I would say that the surprises – some chronic stuff, some genetic things, other things totally out of left field – have influenced both my behavior and my outlook.

I think I am way more apt to be realistic and make choices, do things that are more prudent, than I might if I were unrealistically optimistic. The surprises have taught me to be realistic. I do think it is extremely important to be hopeful because the hope can get you through some very difficult times. When faced with a significant situation, my usual approach is to try to figure out the worst case scenario, identify ways to address that, learn what might be most helpful in solving the problem, and then truly hope for the best.

LikeLike

Hello Helen – thank you for sending your healing thoughts my way. Pondering one’s mortality at age 9 is very young for a child (and to decide that your mother’s life was half over, too!) I wonder if the fact that, although you’ve had lots of “health dramas”, you have come through them all (and even more important, you can look back on those medical crises and feel fortunate about your results.

I like the way you’ve described the difference between optimism and hope. We may not feel genuinely optimistic during a really bad patch, but there is always hope. I too have felt surprised by a number of my own medical conditions – e.g. I was hospitalized for a month when I was 16 – following a ruptured appendix and a near fatal case of peritonitis. When that happens at that age, we stop believing that “bad things don’t happen to me” – because I know they already have – and I survived!

I don’t really see myself as courageous at all as I’m heading into Round 3 of chemotherapy on the 14th – all I’m doing is showing up for oncology appointments and scans and consults and blood tests. When I was told about my one-year treatment plan, I first worried about horrid side effects like nausea and vomiting. I’ve had none at all (but I am on five different anti-nausea drugs!) Some of the chemo side effects are brutal (like bone pain) and some are relatively minor but REALLY UPSETTING quality-of-ife problems (everything I eat tastes disgustingly metallic!) I’m living on frozen fruit pops and ginger ale and protein smoothies. As you say, prepare for the worst, hope for the best.

Take care, Helen… ❤️

LikeLike

WELL you ARE, Carolyn…even as you are facing your cancer diagnosis. When I take my walks, I send you gratitude and love and count your speaking out and caring and self care a gift in my life…

without you, I realise I would have never shared or realised the feelings I had watching my sister be sent home repeatedly when she was in the middle of an aortic dissection which she died of at the age of 45.

I am now close to 76 and your holding space encouraged me to boldly include your resources with women here in the UK, and this past year we won an Inclusion Award here in Cornwall for services to women in menopause….

Please know the ripples of being HEARD and the impact you are and have had. I see you WELL.

With gratitude,

Isabella

LikeLike

Hello Isabella – thanks for your very kind words, and for sending me good thoughts during your walks around Cornwall. I’m so sorry about the tragic death of your sister – and at such a young age.

I visited your beautiful county many years ago, and we still recall that trip fondly – the charming towns and villages, the lovely gardens, the beaches, and of course the people. When I watch Escape to the Country, I love it when they’re house-hunting in Cornwall!

And huge congratulations on your Inclusion Award!!

Take care… ❤️

LikeLike

I think throughout life I have ridden the pendulum of optimism and pessimism full swing in both directions man time. Thankfully, the arc of the swing has become less and less over the years.

A movement towards the middle way. Towards centeredness , I guess towards realism?

Has felt like a blessing a place of peace. A place where the attitude of “This is bad” or “This is good” becomes “This is.” and I will do what needs to be done in favor of Life.

LikeLike

Hi Jill – I like that centeredness concept – like Goldilocks. Not too hot. Not too cold. Just right… I know people who seem on high alert for every new issue, big or small, each gets urgent focus and fretting. and that’s just exhausting. A place of peace seems much less overwhelming!

Take care. . . ❤️

LikeLike

I have always been an early, bouncy optimist. Imagine my surprise when 13 years after bypass surgery, religiously taking all my medications, and being told I was REVERSING my heart disease, I began having recurrent angina and had a total occlusion of my right coronary artery.

Three beautiful new stents later, I was told I have severe coronary artery disease due to a genetic fluke.

Optimism is what contributes to my quality of life! I wake up each day surprised , grateful and hopeful. Cautious optimism for sure: take all meds, exercise, pay attention. And pray for a medicine that can help folks like me.

LikeLike

Hello Dr. Anne – well, your story confirms my own theory that there is no “Fair Fairy” in life! I’m sorry about that genetic fluke and that wonky right coronary artery. You have by now exceeded your lifetime quota of serious medical diagnoses and I really hope that’s quite enough!!

Your situation is also a good reminder to all of us that even when we do everything right, even bouncy optimistic physicians can get sick.

When I was at my Mayo training, there were 45 women like us – all with heart disease, ages 31-71. Our class of 2008 included triathletes, vegans and yes, one physician – all of whom were gobsmacked that heart disease had somehow struck them – of all people!

Take care. . . ❤️

LikeLike