by Carolyn Thomas ❤️ Heart Sisters (on Blue Sky)

Noise is getting in the way of good medical practice and better patient outcomes, according to Dr. Kamran Abbasi, Editor-In-Chief of the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in a recent column he called What is Clinical Noise? – and How to Silence It. But he wasn’t referring to annoying loud noises in our environment, but to unwanted distractions in medicine.

.

Dr. Abbasi illustrates that noise by picturing a dart board with darts sprayed all around the bullseye, distracting players from focusing on what matters to dart players: hitting the bullseye. .

.

He first suggests that

noise must be distinguished from bias – which is systemic throughout medicine. I’ve written for years about

the known implicit bias against female patients in medicine, for example – including excerpts from the important book written by Dr. Alyson McGregor, an Emergency physician and associate professor of medicine at Brown University. Her must-read book is

“Sex Matters: How Male-Centric Medicine Endangers Women’s Health and What We Can Do About It“. .

As Dr. McGregor writes in her book:

“Women are NOT just men with boobs and tubes.”

“We have our own anatomy and physiology that deserve to be studied. One of the biggest and most flawed assumptions in medicine is: if it makes sense in a male body, it must make sense in a female one, too. But in every aspect, our current medical model is based on, tailored to, and evaluated according to male standards.”

I might add a few more words to that last sentence: “Our current medical model is based on, tailored to, and evaluated according to (WHITE, MIDDLE-AGED) males and standards.”

Another example: the highest levels of academic leadership throughout medicine are significantly more likely to be represented by (white, middle-aged) males.

The explicit bias at work here is that men clearly make better leaders than women. This type of bias seems fully conscious. Hiring all those white, middle-aged university presidents is no accident. Academic apologists insist that massive seismic shifts (like hiring women for leadership roles in medicine) simply takes time for our culture to adapt or accept.

And after all, it took until 2016 for Oxford University to hire Dr. Louise Richardson as their first female president in its entire 767-year history.

And according to University Affairs, men still hold 69 per cent of university president posts here in Canada, where I live. Among our most research-intensive universities, that figure rises to 87 per cent. Diversity is known to be a key factor in both identifying talent and running a selection process on campus. And a lack of that diversity is often the culprit in disproportionately favouring candidates who look just like all other past candidates.

Yet implicit bias is unconscious, meaning we can be equally biased against certain people or groups of people despite such bias being entirely outside of our conscious awareness. Compare that to explicit bias in which we are well aware of our own biases against those people or groups – and don’t even pretend to be unaware.

.

Outside of medicine, let’s talk math as an example of implicit bias in that specific field. Harvard University’s

Project Implicit suggests that even if you believe that men and women are equally good at math, it is entirely possible that you associate math with men – even without knowing it, according to Harvard researchers who added:

.

“In this case, we would say that you have an implicit math-men stereotype.”

.

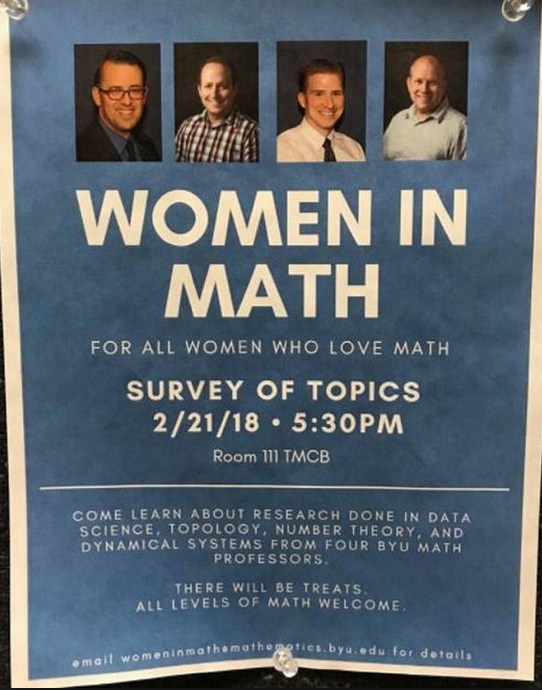

Speaking of math, I cannot possibly mention math and implicit bias in the same sentence without including this poster distributed at Utah’s Brigham Young University in 2018 – clearly the poster child of implicit bias in academia. I’m guessing that, based on the four head shots featured in this poster, none of the smiling white males would admit to either an implicit or explicit math-men stereotype (yes, even when you title your poster event “WOMEN IN MATH”!

I love this poster so much (and not because Brigham Young University was essentially announcing its inability to find even one competent female mathematician on its faculty to speak at a Women In Math event) but because it’s such a perfect example of how clueless even brainiac mathematicians can be when it comes to creating that superfluous NOISE that Dr. Abbasi warns his colleagues against.

.

Everything about this poster is noise – from the male-only professors to the jarring array of their smiling faces directly above that Women In Math event title. Each was needlessly distracting noise that stops readers in their tracks, disoriented by the obvious discrepancy between the title and all those men.

.

This poster reminds me of other well-meaning NOISE when The American Heart Association hosted its first public conference for women in the 1960s – but it was called “How Can I Help My HUSBAND Cope with Heart Disease?”

.

Remaining in medicine, another classic example I’ve covered here was a U.S. study whose conclusions on implicit bias made my brain explode when I first learned about it the year after that unfortunate Women In Math poster.(1)

.

The American researchers had studied the database of the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (which collected pre-hospital patient care reports from 46 U.S. states) over a three-year period.

.

Their extensive data included 2.4 million men and women experiencing chest pain who had been transported by ambulance to a hospital after calling 911. But the most shocking part of this study was this conclusion, published in the journal, Women’s Health Issues:

“When transporting women with cardiac symptoms from the scene to the hospital via ambulance, Emergency Medical Services personnel were significantly less likely to use flashing lights and sirens compared with men being transported.”

For more on this landmark study, see also: Fewer Lights and Sirens When a Female Heart Patient is in the Ambulance.

.

Were all of those ambulance drivers experiencing explicit bias in which they genuinely believed that lights and sirens are somehow not required if a woman is the one being transported in “the back of the bus”? Or could they be experiencing implicit bias in which they are simply unconscious of their own decisions to treat certain patients (men) in ways that are not being applied to female patients?

.

Dr. Abbasi also warned in his BMJ column how implicit bias tends to skew clinical decision-making in one particular direction. His example: when doctors have a financial interest in the business success of a particular medical procedure, drug or device, and might recommend those choices to patients over equally good or even better ones.

.

He adds that this clinical noise is an expression of the variability in care that health professionals can provide to patients:

.

“This is important because a central objective of health care should be to reduce variations in care. And this is why we need to appreciate the existence of clinical noise, and how we might reduce it.”

.

Yet Dr. Abbasi is hardly optimistic about an issue most of us are familiar with: our senses and attention spans are bombarded by information – particularly from social media, as he explains:

.

“One particular focus of social media advice, most notably in relation to wellness, has implications for management of many diseases. The demand for such advice is huge on social media platforms. People are hungry for information. However, the quality of advice is open to question, and requires better moderation and possibly regulation. Yet pulling us back from the social media noise of misinformation, commercialization, and exploitation seems an impossible situation to retrieve.”

.

Historically, he says, the practice of medicine was a simpler affair in terms of options available to clinicians, but the trade-off was a greater degree of guesswork in terms of diagnosis and management:

.

“The pioneers of clinical practice and research managed to shut out the noise and drive for improvements. Is it possible for us to do the same today when the noise is louder and improvements harder won?”

.

1. Lewis, Jannet F. et al. “Gender Differences in the Quality of EMS Care Nationwide for Chest Pain and Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest.” Women’s Health Issues, December 10, 2018.

♥

Q: Do you believe you have no implicit bias? Just for fun, take Harvard University’s free Implicit Association Test to find out.

.

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote much more about the known differences between how male and female patients are researched, diagnosed and treated in my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease” . You can ask for it at your local library or favourite bookshop, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon, or order it directly from Johns Hopkins University Press (and use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price when you order).

Like this? Share it with others!

Carolyn, I so appreciate the way you take Dr. Abbasi’s concept of “clinical noise” and ground it in vivid, real-world examples. Your writing makes me reflect not only on patient care but also on the broader systems that perpetuate inequity.

Marie Ennis-O’Connor

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Marie – thank you for your kind words, and for reminding us that this “noise” is not limited to patient care but to so many scenarios in our society.

Take care. . . ❤️

LikeLike

Hello Carolyn,

One of the ways bias slips into medical practice is when patient symptoms don’t match what is deemed typical for a particular disease. As in women with unusual cardiac presentations that don’t match the symptoms reported in male dominated research( as you have written about many times).

Also, the strength of women’s intuition about their own bodies is not quantifiable in medical research therefore it is assumed to be invalid.

I’ve been having discussions for the past year with my cardiologist about low grade pressure in my chest on and off and at rest.

Last week I asked him isn’t there a test like a CT scan that could tell if my CAD is progressing? I FEEL like there is a coronary artery slowly closing up and I rather not wait until it becomes a heart attack.

Surprise of surprises, he took me seriously and decided to call it atypical angina and ordered a cardiac Cath.

I sit here today, 48 hrs post double, end to end stents in my right coronary artery.

Heart attack averted.

LikeLike

Wow Jill – what an amazing example of your intuitive “knowing” something was very wrong!! – and even better, finally your cardiologist taking your strong intuition seriously. I’m so glad you were persistent in convincing your doctor – and also that he was finally open to believing you after that long year! I hope you feel so much better now that your artery is gloriously unblocked!

I’ve been reading Dr. Kelly Turner’s book, “Radical Remission” based on her PhD thesis in which she studied over 1,000 cases of people diagnosed with terminal cancer who had experienced unexpected spontaneous remission of their tumors. She identified nine factors that these patients had in common – one of which was “followed intuition” – just as you did 48 hours ago!

I’ve known for a long time that my own intuition has guided me both toward or away from various decisions over the years, and whenever I have chosen not to listen to that intuitive voice, I inevitably regretted it later!

I’m so glad you listened to the voice that was telling you how to avert a heart attack!! My therapist would call your doctor’s surprisingly positive response to your “feeling” that the coronary artery was slowly closing up as the result of what can happen when we communicate with our authentic voice.

I had a similar experience when new side effects of my chemotherapy hit me (a painful condition called Hand-Foot Syndrome: peeling blisters on both feet caused by the chemo drugs seeping through the walls of blood vessels into healthy tissues). The blisters were so brutal that I’m now using a walker. I told my oncologist I simply could not bear to show up at my scheduled chemo appointment (which would have been tomorrow) to restart the same chemo drugs that had caused those horrible symptoms in the first place. I’d mentioned side effects before, but I think I’d been using my ‘good patient’ voice (minimizing my symptoms) – until the last visit when I pulled no punches to describe why I needed a break from chemo. I too felt surprised when he took me seriously and agreed to a couple weeks off. And he’s reducing the chemo dosage by 15% when I reschedule my next Chemo Day to August 18th!

So no more ‘good patient’ chats… 🙂

Take good care of yourself. . .❤️

LikeLike

Yes, AUTHENTIC VOICE! That voice comes directly from your soul and KNOWS what needs to be done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Carolyn – such an intriguing concept: how NOISE needlessly makes common sense reality confusing and overwhelming for patients. Every day I witness nurses doing our best – we’re dancing as fast as we can. It doesn’t have to be like this. I’ve been a nurse for decades, approaching retirement very soon, and have seen first hand how the pointless NOISE of ineffective and ever-changing bureaucratic policies and protocols from ‘on high’ can often allow patient suffering to continue or even worsen. Those bureaucrats should be condemned to a few weeks as hospital patients.

I’m sorry about your recent breast cancer diagnosis, and especially your example of being ignored by hospital staff in last week’s column. Keep up the good work you do (within the gentle limitations of self-care of course!) and good luck in your treatment plan.

xo

LikeLike

Thank you RN in NYC – I love hearing from nurses working in the trenches, and I wish that the ineffective hospital policies you mention could somehow be creatively re-imagined to improve that NOISE scenario for both patients AND professional staff.

Take care. . . ❤️

LikeLike