I could make out the rounded corners of the implanted device stretching through the thin white skin of Ann’s chest. I was shocked to see such a young, healthy-looking woman among our Heart To Heart survivors’ support group that night (we were vastly outnumbered by old men and their wives). Ann (not her real name) was just 24 years old; her younger sister had recently died of sudden cardiac arrest due to a terrifying heart condition called Long QT Syndrome – a heart arrhythmia usually affecting otherwise healthy teenagers and young adults – whose first symptom is sudden loss of consciousness and, in far too many cases, death.

Because there is often a family connection, all of the surviving siblings in Ann’s family had to be tested to see if they too shared this deadly diagnosis. Her brother was fine, but Ann tested positive for Long QT, and so was immediately implanted with a life-saving cardiac device called an ICD.

Until that evening when I first met Ann, I’d never even heard of ICDs. As described in the journal Circulation:

“An Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) is an implantable biomedical device that monitors and treats abnormal heartbeats when they occur.

“The device is attached to the heart with 1-3 leads that carry information from the heart to the ICD, allowing it to record heart function, selectively provide pacing if the heart beats too fast or too slowly, and/or administer high-energy shocks if more serious heart rhythms are detected.

“The primary purpose of the ICD is to prevent premature sudden cardiac death. However, the device can also provide a sense of security, which allows resumption of normal life activities.”

Not every person who has an ICD implanted has a Long QT diagnosis. For example, any patient at risk of developing sudden cardiac arrest due to heart arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia, Brugada Syndrome or fibrillation may be a candidate for an ICD.

You might imagine that it would feel reassuring to have what’s essentially a built-in cardiac crash cart implanted right inside your chest to save your life in case of sudden cardiac arrest.

But research suggests considerable psychological distress can occur in both ICD patients and their partners.

For example, a University of Florida study(1) published in the Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention looked at levels of death anxiety, shock anxiety, general anxiety and marital adjustment of the participating couples when one of the pair had an ICD implanted. Researchers found that anxiety may actually be more common in ICD partners than in ICD patients themselves.

Partners were particularly worried about ICD shocks, even more so than the patients. Interestingly, female ICD patients reported more anxiety related to both dying and being shocked than male patients did – perhaps because women actually did receive more shocks from their ICDs than men did, despite equivalent levels of medical severity.

Another study(2) reported in the journal Circulation looked at important lifestyle adjustments that must be made to promote health and wellbeing for both ICD patient and spouse:

“Such adjustments may take time and a bit of work; most people take about three months to adjust to such major life changes. A patient’s adjustment often mirrors the partner’s adjustment, so effective coping can improve both of your lives.

“Patient acceptance refers to how well an individual adapts to the ICD and accepts its pros and cons. Patients and partners may differ on how well they accept the device.

“The hope for ICD patients is that they re-engage with the confidence of having ‘an emergency room in the chest’, yet some patients experience difficulty and avoid activities they previously enjoyed, such as going places or interacting with other people.

“In fact, both ICD recipients and partners may experience distress caused by fear of shock, body image concerns, or fear that the device will malfunction or be recalled.”

Some partners report feeling helpless as they anticipate their loved one receiving an ICD shock. Other partners fear shocks happening in public, and this fear can lead to avoiding social situations, even though research indicates that shocks cannot be induced by participating in normal activities of daily living like exercising or visiting with friends, nor can they be avoided by cancelling these activities.

Sometimes, in an attempt to protect the patient, a partner may inadvertently prevent the patient from returning to a full lifestyle. And with the focus of concern on the patient and the patient’s medical condition, some partners may also find it difficult to discuss their own concerns, convinced that their own worries pale in comparison to those of their partner.

When either member of a couple withdraws from social or physical activities because of anxiety, the other will tend to withdraw as well. Both partners and patients often withdraw under the misconception that they are helping to prevent or reduce the chance of ICD shock. Disagreements over the patient’s eating habits, dependence or independence, activity or medical decisions are very common and may cause tension among couples, but these disagreements are typical of the ongoing process of adjustment.

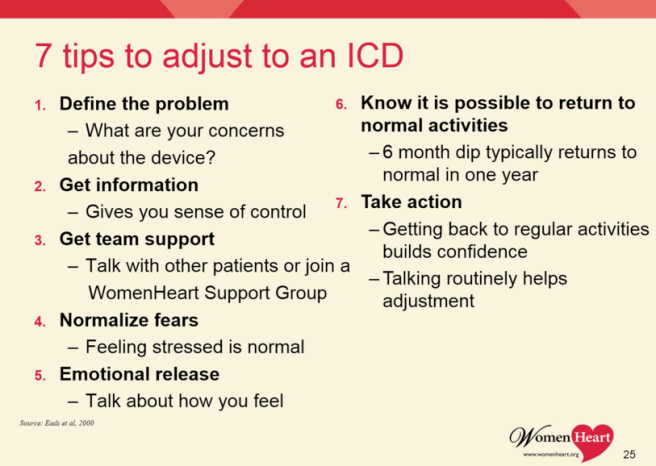

And here’s what cardiologists want patients to know about adjusting to an ICD (via WomenHeart: The National Coalition For Women With Heart Disease)

♥

.Researchers offered these important suggestions to help patients and their partners adjust to living with an ICD:

- learn as much as possible about the ICD

- acknowledge the benefits of living with an ICD

- use the expert support of health care providers

- assist your loved one in performing daily and ICD-related tasks

- discuss each other’s changing roles in caring for ICD-related matters

- focus on the positive aspects of caregiving

- be assertive in expressing your struggles

- learn and implement relaxation techniques

- learn how to respond to ICD shock

- seek support in each other as well as in ICD support online or in groups

- know when to seek professional help

- participate in physical and social activities

- listen, be patient, withhold judgements

- seek subtle ways to become more intimate – take it slow!

- encourage the patient to live life fully while doing activities previously enjoyed

- inform children/ family members about shock and how the ICD works

This study’s researchers summarize by reminding us that partners of ICD patients may face difficulties on several fronts including:

- caregiving expectations

- learning about the ICD

- managing stress related to the future of living with cardiac disease in the partner

Doctor appointments, health education, and frequent discussions about necessary changes may be an unwanted reminder about a partner’s heart condition, they add.

“The goal for both people is to achieve a high quality of life because of the protection that the ICD provides. A good quality of life is obtainable when the patient and the partner, along with the help of friends, family, and health care providers, can work as a team.

“Together, this goal can be reached by adjusting to life with an ICD, avoiding or managing psychological distress, and maintaining healthy relationships and activities.”

♥

(1) L. Sowell et al. Anxiety and marital adjustment in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator and their spouses. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007; 27: 46–49.

(2) Coping With My Partner’s ICD and Cardiac Disease. A. G. Hazelton, S. Sears, K. Kirian, M. Matchett, J. Shea, Circulation. 2009; 120: e73-e76.

l

See also:

- ICD Warning: Defective “Riata” Defibrillator Leads Recalled

- What sudden cardiac arrest looks like

- What heart patients want ICD makers to know

.

Q: How have you and your partner adjusted to life with an ICD?

by

by

Not my partner but my 82 yr old father, who lives with me. He had an ICD fitted Oct ’15 so is still in the 6 month ‘take it easy’ period. He has a very positive attitude & is coping well with having to slow down for a bit (apart from not being able to drive his tractor), lucky that it happened during the winter.

I am just trying to arm myself with the info and tools to deal with any major episode. Unfortunately docs seem to think they need to give you chapter and verse on everything – much of which gets lost on me. Any pointers to concise info that will help me?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Liz and thanks for sharing your Dad’s (and by definition, your) experience here. My first observation is this: never ever be reluctant to raise your hand during any “chapter and verse” medical explanation you do not fully understand! Ask for a Plain English translation. Most doctors who tend towards medical-ese may not even be aware that listeners aren’t ‘getting’ it, especially if the listeners are sitting there politely and not interrupting.

I like this article which covers a lot of the basics of life with an ICD. Also, although de-activating your Dad’s ICD at some point if he becomes very ill may not be even remotely on your radar at this point, this is an important and often-overlooked topic for all elderly ICD patients to know about. Dr. John Mandrola has written extensively about this issue and is a great resource. Best of luck to both you and your father…

LikeLike

I am just currently learning myself, I had suffered SADS this past January and they put an ICD in me. Thanks for this post it is always helpful to read more information.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment here. For the benefit of our readers, SADS is Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndrome, a genetic heart rhythm condition that can cause sudden death in young, apparently healthy people. Luckily, you have your ICD implanted now, but you and your family are still in relatively early days yet in adjusting to life with an ICD. Good luck to you!

LikeLike

Thank you and yes we are still very new to all of this and we are slowly adjusting.

LikeLike

I was wondering as well if you recommend any other blogs that I could follow, that others suffered the same or just with heart conditions??

LikeLike

I’m not familiar with specific SADS or ICD blogs, but if you haven’t already done so, you might want to check out Inspire.com’s WomenHeart online support community which has two topics of interest to you: Younger Women With Heart Disease as well as one called All About Arrhythmias.

LikeLike

Thank you for the website, I will check it out 🙂

LikeLike

It is my experience that all cardiac events have collateral effects on family, friends, loved ones. Most of those are “feelings”, in reality very strong emotions, and are unacknowledged by our present medical providers.

As an example, during rehab I was twice reminded that I could begin having sexual intercourse in six weeks – but never was the breast paresthesia and hyperesthesia (pain) mentioned, nor the normal fears of death during sex, nor advice about sexual positions that would be least difficult for someone with a sternotomy that is still healing.

I think that counseling should be part of cardiac rehabilitation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your perspective, Anne. You are so right. I suspect this is because cardiac care is largely still provided as if it were merely acute medicine – like getting a list of wound care instructions – with little appreciation for the emotional trauma that survivors can experience.

I agree – counseling should indeed be part of every cardiac rehab program, yet up to “90% of programs report having no dedicated psychology time for their patients” according to Heartwire. Dr. Kathryn King‘s research on cardiac rehab programs – and specifically women’s high dropout rate – has reported: “Many women don’t find rehab programs relevant to their needs, suggesting that women may find programs more appealing if there is a strong psychological emphasis, rather than exercise being the main focus, as is currently the case.”

LikeLike