by Carolyn Thomas ♥ Heart Sisters (on Blue Sky)

“Havoc” /hævək/ Oxford Dictionary definition: “a situation in which things are seriously damaged, destroyed or confused.”

October is officially Breast Cancer Awareness Month – and this month, it’s also my first time as a person diagnosed with malignant breast cancer. So I’m feeling more aware of breast cancer than I’ve ever been. (Think: six rounds of chemotherapy, 11 more scheduled rounds of immunotherapy infusions, countless scans, blood tests, oncology consults, a port surgically implanted in my chest, plus the mastectomy booked for November 25th. Oh, joy. . .) And I’m telling you right now, enduring chemo side effects has been even more brutal and debilitating than I could have imagined, a genuine quality-of-life nightmare in action. The powerful chemo drugs that are pretty effective at killing off fast-growing cancer cells are the same drugs that are also killing off my healthy cells, wreaking havoc on my body now and perhaps for months or even years to come. Buckle up, buttercup. . .

That word “havoc” also got me thinking about the late women’s health activist Barbara Brenner (a breast cancer patient herself). She’s best known for her many years of breast cancer activism as the Executive Director of a remarkable organization called Breast Cancer Action.

After Brenner died in 2016, the venerable U.K.-based medical journal The Lancet described her in their obituary column as a “true hell-raiser (a splendid job title, I thought!)

Further eloquent obituary testaments to Brenner’s life and work followed. For example:

“As the very visible spokeswoman for Breast Cancer Action, she maintained her post-chemo hairstyle, and, after her mastectomy, her unreconstructed chest. She wasn’t a survivor so much as a living testament to the life-long effects of breast cancer and the toll that it takes on all of us.“

Brenner’s raw and uniquely personal take on “the life-long effects of breast cancer and the toll breast cancer takes” was apparently rarely heard in breast cancer circles at the time, and that reality reminded me of another famous Barbara.

The late Barbara Ehrenreich was a prolific investigative journalist (and also a breast cancer patient) and the author of over 20 books. Before her death, I read one of my favourite Ehrenreich books called Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Undermines America

That book title may seem bizarre if you believe, as many do, that positive platitudes are helpful to cancer patients. Yet we know that every cancer is different. Every cancer patient is different. Every response to a cancer diagnosis is different. For me, the cover of Nancy Stordahl’s excellent memoir of her own breast cancer experience says it all: “Cancer Was Not a Gift and It Didn’t Make Me a Better Person!” (Best title ever!)

I can also tell you that my public relations colleagues working in breast cancer fundraising have done a remarkable job of raising both awareness and money for their cause. So remarkable, in fact, that many if not most women have been mistakenly convinced that breast cancer is our deadliest health threat.

It was only after surviving my own misdiagnosed widow-maker heart attack that I learned heart disease kills 1 in 8 women each year, compared to 1 in 36 who die from breast cancer. Survival rates among patients diagnosed with breast cancer now hover around 90 per cent.

Still, every breast cancer diagnosis is one too many.

Optimistic statistics, by the way, do NOT mean this diagnosis isn’t overwhelmingly, often unbearably, horrible for many of us. Unlike my heart attack experience (and most other diagnoses in which we feel really bad until our treatment starts), I felt perfectly fine when I was diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma. I’ve heard women diagnosed with breast cancer report that they are more afraid of the treatment than the cancer itself.

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) reported that, beginning with their breast biopsy, women almost always describe the time period between the biopsy itself and the availability of their pathology results as the most psychologically distressing time period during their entire cancer experience. Anxiety reportedly reaches its highest pitch at the moment those biopsy results are actually discussed with patients. As one breast cancer patient explains that anxious wait:

“While waiting for my biopsy results, my son called and asked what I was doing. I told him I was waiting to find out what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

The NLM authors add that, in its broadest sense, breast cancer is a disease that affects every area of a person’s life – with accompanying emotional, physical, mental, psychosocial and sexual complications that are “not always appropriately addressed by healthcare professionals.”

Barbara Ehrenreich shared a compelling story in her Bright-Sided book about attending her first breast cancer support group. She was dismayed to discover that the otherwise pleasant group members seemed unwilling to even acknowledge her valid worries. She was repeatedly reminded by others in the group of the need to “think positive!” at all times. Ehrenreich added:

“Here I was, 59 years old, facing the worst crisis of my life, and there was nothing empowering, no trace of the bold women’s health movement I knew back in the 1970s. In fact, I got a response from one woman who suggested I run, not walk, to the nearest therapist, and that she would pray for me, because I needed to work on my ‘bad attitude’ if I wanted to live.”

Since then, I’ve been told even by (freakishly cheerful) strangers that I’m “lucky” to have cancer, because now I know for sure that I must “live life to the fullest” every day (as if my meaningless cancer-free self did not know that).

I find that profoundly insulting – particularly coming from people who don’t know me.

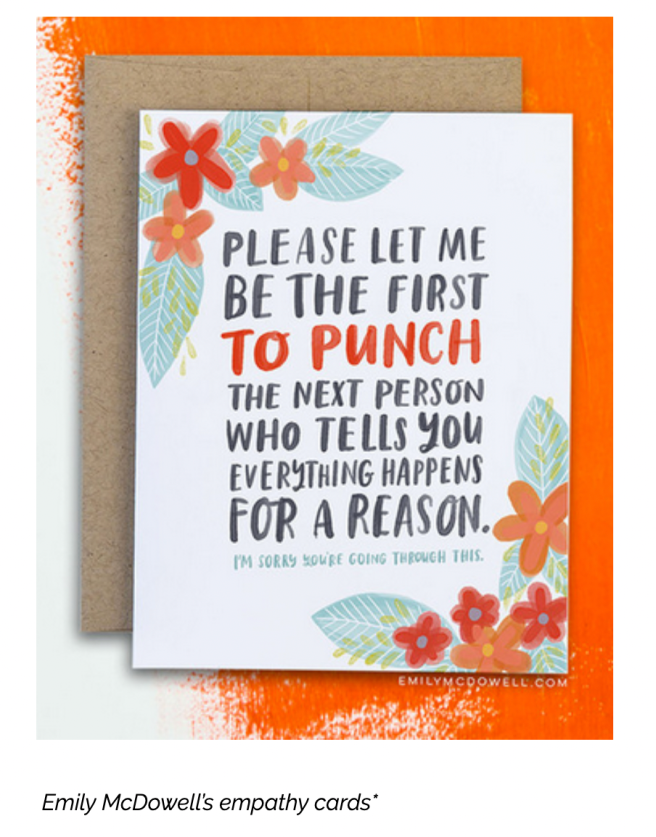

My humble advice: don’t ever tell freshly-diagnosed cancer patients they are “lucky”. If you need to believe that about your own cancer diagnosis, fill your boots – but meanwhile, please try to share compassion instead of uninformed opinion.

What might you say instead? I like what the Canadian Cancer Society site recommends – offering a simple kindness like: “I am so sorry that you have to go through this. I know treatments can be very difficult. I’m here to support you.” That lovely sentiment (along with a weekly trip to the ice cream store) can really help.

♥

FYI: More here about my breast cancer updates.

.

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote much more about becoming a patient (no matter the diagnosis!) in my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease”. You can ask for it at your local library or favourite bookshop (please support your neighbourhood independent booksellers!) or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon – or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

Thank you, Carolyn. I am so sorry you are having to go through this. I appreciate all those references to books, like Barbara Ehrenreich’s Bright-Sided … I remember a time when my mom, who had had breast cancer, multiple strokes, and rheumatoid arthritis, was dying in a nursing home. She was paralyzed in several areas, could not communicate effectively, could not feed herself, all sorts of limitations. It was AWFUL. But there were people who came to visit who could not fail to put on a cheerful perky happy face, and mutter platitudes about all the positives. I know there were plenty of things to be grateful for, regarding her situation, but overall, the situation was awful and I wanted to slap the perky smile off of those who exuded the fake saccharine cheerfulness.

I think there is an honesty component here – I personally find it much more helpful to name whatever the havoc or desperate situation is. Acknowledge it and then, and only then, are you able to consider moving past it. Last Christmas, I had a bad breast MRI and had to wait until after the holiday to get the follow up tests, which fortunately turned out fine. It was excruciating to wait and live in the uncertainty. And there is real physical torture, for lack of a better term. Once, after oxy was given for spinal pain subsequent to a brain bleed, subsequent to a heart attack, my bladder stopped working. It took four doctors 16 attempts to insert a urinary catheter. So – there’s no way to sugarcoat some of this. Let’s be honest and speak truth.

I hope, Carolyn, that your path becomes much easier soon.

LikeLike

Hello Helen – oh my! 16 attempts to insert that catheter?!?!? THAT is torture! You’re so right – no way to sugar-coat incidents like that – and trying to look on the “bright side” of patient care that’s painful instead of helpful just seems insulting. Sometimes THERE IS NO BRIGHT SIDE! Before I had a port surgically implanted into my chest to replace the regular IVs previously used during every chemotherapy appointment, I was shocked by the wide variation in skills between chemo nurses – some could pop that IV in expertly every time, while others had to try repeatedly (clearly growing more frustrated with every failed jab while ignoring the growing discomfort of the poor patient!) In my old life (pre-chemotherapy IVs) I would have laid there suffering silently while staff practised on me. But over time, I decided to try my best to avoid suffering at all times if I could possibly intervene – even when that required asking for the most experienced and skilled chemo nurse to step in. My retired nurse friends tell me that at one time, hospitals used to have Specialty IV teams, on-call for every IV placement. The more IVs they did, the better their skills generally were – and vice versa. Unfortunately, our cancer clinic doesn’t seem to have those specialty teams anymore – which is why my first Nuclear Medicine tech advised me: “If they ask you if you want a port, SAY YES!!”

Thanks Helen for your kind words. . . ❤️

LikeLike

Carolyn, my heart sank when I read that you have to endure a mastectomy. I cannot fathom any reason that would justify this horrible ordeal of malignant breast cancer. Those who reduce it to a callous platitude like, “Everything happens for a reason” deserve a response like, “Are you saying that to make you feel better or to make me feel worse?” ‘

I imagine they “mean well,” but the mean part comes through the loudest. I am sure I am among the multitudes who are sending you love and gratitude for the support you provide for women facing heart disease and breast cancer. We are rooting for you from all across the globe!

LikeLike

Thank you Marie for your kind words. I know that most people do mean well when coming up with those trite platitudes – but it’s likely more that they simply don’t know what to say. They aren’t deliberately thoughtless – they are just not being thoughtFUL.

Take care…❤️

LikeLike

My mom is currently undergoing treatment for breast cancer. She had 3 surgeries and is now doing chemo and radiation. It’s been such a hard thing. Helping her through the sickness and pain, making sure she gets to her appointments and taking notes so she doesn’t miss anything. I truly wouldn’t wish it on anyone or their loved ones.

LikeLike

Hello Megan – I’m sorry that your mother’s been diagnosed with breast cancer. It’s so hard to watch the people you love when they are suffering, and it’s also hard for mothers who are the patients to watch how upsetting and worrying this can be for our children. Our families want and need us to be “better” – which is what we want too of course!

I know that my own family helps me so much during the worst of these times. My daughter also takes notes and drives me to my Cancer Clinic appointments and is just being a wonderful support person for me.

(Although this weekend, the horrid chemo side effects include losing my fingernails (which I’ve been warned about by my oncologist for months – “You will lose your fingernails, and it will be painful”. But today the pain was so unbearable (the fingernails have “lifted” and look like they’re infected – rotting from under the nail bed; if I touch the nails, some kind of fluid seeps out from underneath the nail – completely disgusting and excruciating!

My oncology nurse recommended I see a doctor ASAP for a swab and possible antibiotics – I have an appointment later today.

She made this casual comment over the phone: “Hmmm… I knew my chemo patients often lose their nails, but I’ve never followed up afterwards to see what it’s really like…”

I think that every oncologist and every chemo nurse should be invited to wear Ice Mitts for even one hour to “see what it’s like”. Despite one hour during every chemo day for months wearing special Ice Mitts – which are supposed to prevent fingernails from falling out – the Ice Mitts are clearly NOT WORKING!)

And wearing Ice Mitts for one hour every Chemo Day is an incredibly painful torture all by itself. Despite all the hours I’ve spent in the chemo room wearing those Ice Mitts, I find myself in agonizing pain now with no relief except to take Extra-Strenght Tylenol – and hopefully get some prescription antibiotics. Take care. . . best of luck to your Mother. ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you feel better and heal fast! ❤️❤️❤️❤️ sending ALL my love!

LikeLike

Thank you Megan. . . ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Twenty four years ago, I had two consecutive years of breast biopsies, which thankfully, were negative for cancer. Not long after I got through that experience, I went into the ER with what I thought was a broken arm and learned I had a tumor in my right humerus bone. First suspected to be a sarcoma, it later turned out to be skeletal Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma. I was astounded. I thought if I had just worried about breast cancer and took care of that, I didn’t have other cancer worries. That is so untrue. There are so many types of cancer and I want to assure you that none of them are good.

I survived bone cancer in spite of having already been a Type 1 diabetic for 47 years at that time. Six chemos, major surgery on my arm, one month of radiation and I was grateful to be cured. But the bone cancer chemo left me with heart failure, a heart attack and a stent. And osteoporosis. I am unable to take any bone density medications because they make me very ill.

The moral of my story is that you should never just focus on preventing just one type of cancer. You’re human and you are vulnerable to them all and not one of them is pleasant. Be vigilant and get your check-ups.

LikeLike

Hello danechick – what an ordeal you have survived, and one thing after another after another, all piled on top of each other. I’m so sorry that your chemo caused your cardiac diagnoses.

I’m thinking you have by now definitely reached your maximum lifetime quota of dreadful medical crises and deserve to put your feet up and have some peace. According to Mayo Clinic, the exact cause of most breast cancers isn’t known – no matter how much we may want to focus on prevention. But it’s not clear why some people who don’t have any risk factors often do get cancer, yet others with known risk factors often don’t.

On paper, I would have thought my own risk of breast cancer was pretty minimal (I had no family history, I’d breastfed both my babies (for 20 & 22 months respectively), I had a ‘normal’ menopause at age 50, I don’t smoke or drink alcohol, I was a distance runner for almost two decades, etc etc etc – and still I end up with a malignant breast tumor the size of a “small grapefruit”. Apparently, being female and getting older are the two key risks for breast cancer.

LikeLike

This brings to mind Kate Bowler’s wonderful book title, Everything Happens for a Reason and Other Lies I’ve Loved. Also a great read with her bold discussion of toxic positivity.

LikeLike

Hi Sara – Thanks for that Kate Bowler book recommendation – another great title!

I will look for it today! Take care. . .❤️

LikeLike

Thank you for weaving in the legacies of Brenner and Ehrenreich, whose refusal to prettify this disease helps us all stay honest. Your reminder to choose compassion over clichés is a gift. Marie Ennis-O’Connor

LikeLike

Hello dear Marie – I’m relatively new to breast cancer (diagnosed in April) but that word “prettify” is right on the money. At “Run for the Cure” fundraising events, organizers seek out only happy, positive, brave and appropriately grateful heroic role models onstage for crowds to cheer on. Women whose cancer has spread are not what event crowds want to see… Just the safe pretty pink stuff…

LikeLike