by Carolyn Thomas ♥ @HeartSisters

When my heart sister Katherine Leon was featured in The New York Times earlier this year, I was thrilled. Katherine, like me, is a graduate of the WomenHeart Science & Leadership patient advocacy training at Mayo Clinic. She told the Times of undergoing emergency coronary bypass surgery at age 38, several days after her textbook cardiac symptoms had first been dismissed by doctors who told her, “There’s nothing wrong with you.” .

That misdiagnosis, sadly, is not uncommon – especially among women in their 30s. And the type of severe heart attack Katherine survived (Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection, or SCAD*) is particularly tricky because it tends to strike mostly women, mostly women younger than 50, and mostly women who have few if any known cardiac risk factors. These women simply don’t fit the profile, as I’ve written more about here, here and here. I’m re-visiting this NYT piece on SCAD after encountering an increasing flurry of harrumphing physicians on social media who are clearly feeling defensive about all this talk of gender bias in medicine.

Many, many studies have shown that female heart patients are significantly more likely to be under-diagnosed – and worse, often under-treated even when appropriately diagnosed – compared to our male counterparts. See also: Ms. Understood, the 2018 Heart and Stroke Foundation eye-popping report on women’s heart disease, or this 2019 editorial in the U.K. medical journal, The Lancet.

SCAD was at one time considered to be a rare heart condition. But as Dr. Sharonne Hayes (a respected Mayo Clinic cardiologist, founder of the Mayo Women’s Heart Clinic, longtime SCAD researcher and also a featured expert in the New York Times piece) now says, SCAD was not rare, but rarely correctly diagnosed for decades.

Yet as important as this Times article is in helping to raise awareness of SCAD in women and their physicians, it was the public response to the article that floored me.

And when I say “the public”, I mean the response from physicians.

I was gobsmacked by reader comments like the following, from those who are clearly annoyed by even the mention of gender bias in medicine.

♥

◊ Chris (New Jersey): “I work in an emergency room. No one’s symptoms are trivialized because of their gender. That is absolutely ridiculous.”

◊ KSK (Maine): “I am an Emergency physician. I am aware of bias in medicine against certain groups and I strive to avoid it in my own practice, but I feel articles like this confuse bias with diseases that are made difficult to diagnosis based on their rarity and/or unusual symptoms. Also worth noting is danger of over-testing, especially invasive testing. It’s a difficult problem for medicine, but I am not sure how much of a role gender bias plays.”

◊ John Wesley (Baltimore, MD): “This is OLD NEWS. 2003 was more than just 15 years ago, it was a generation ago in terms of having access to troponin testing , sophisticated heart scans, ultrasound at the bedside, and widespread certification and training in emergency medicine. Heart attacks in 40-year old postpartum women simply don’t commonly get ‘written off’ by sexist, uncaring doctors. I think it IS important to alert female patients that they can have heart disease at a young age, and we do need to fund more gender and age specific studies in medicine, but if you have symptoms like this woman had and you go to Emergency in 2019, you will get the care and diagnosis you need. It has nothing to do with medical school curriculum, physician ‘wokeness’ or mysogyny.”

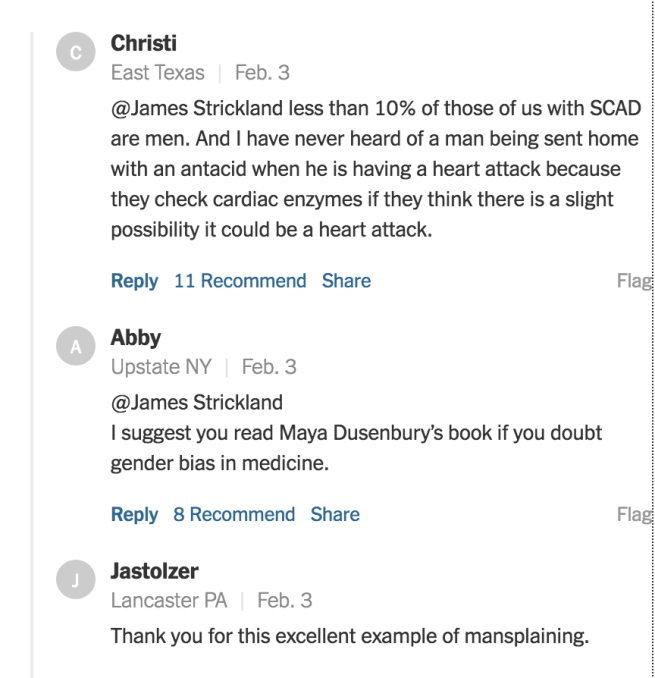

◊ James Strickland (Wilson, NC): “This is an inflammatory article that has no basis for declaring there is gender bias. SCAD also is even rarer in men but does occur. If the diagnosis is missed on a man, can one claim gender bias? I think not.” .

♥ CAROLYN’S NOTE: Strickland’s comment could not be left alone, as this sampling of New York Times reader replies quickly demonstrated:

Gender bias deniers, especially those who self-identify as physicians, apparently embrace some version of“If I don’t know about it, it does not exist!”

A variation on this theme that I’ve heard over the years: “It does not exist because I said so!”

Or, slightly more frequently, this semi-enlightened insistence: “Yes, I’ve heard that this gender bias may in fact exist, but certainly NEVER in my own hospital/clinic/practice or in anybody I know personally!”

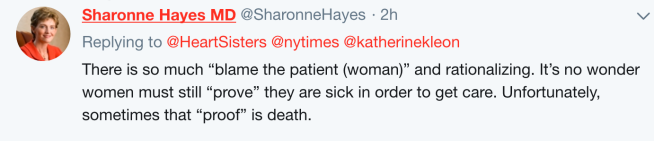

When I objected on Twitter to those hostile Times reader reactions, especially coming from intelligent, educated physicians, Dr. Hayes tweeted back:

And for Times readers who continue to insist that the dangerous misdiagnosis that happened to Katherine Leon could not possibly happen today, consider the far more recent experiences shared by the following NYT readers suggesting that, yes, indeed, it can and it does:

◊ Nicole Miller (Connecticut):

◊ Holly (Ohio):

“I sat in the ER for over 3 hours having a heart attack before the troponin results came back. And it took them another 2.5 years and another heart cath before they decided that it hadn’t just been an unusual type of clot but had actually been a SCAD (in 2014 and 2017 respectively). They still have so much to learn.”

♥

All may not be as bleak as those New York Times responses might lead you to conclude.

I was, at the end, heartened to read, despite the knee jerk defensiveness of some physicians listed previously, that there were also a number of supportive comments from other docs like these:

“I will never forget the patient I admitted to the ICU with acute respiratory failure and acute congestive heart failure in the setting of an acute MI (heart attack). After she was stabilized, I looked over her medical records and saw she had been in the emergency room 5 days prior to coming in to my service in extremis. Her chief complaint 5 days earlier: ‘I’m having pain in my neck like when I had my heart attack.’ Treatment: No EKG, no labs, but a prescription for Valium. It is sometimes down right criminal. Hysterical woman.”

♥

*How does Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) happen?

According to The SCAD Alliance:

“The inner lining of the coronary artery splits and allows blood to seep into the adjacent layer, forming a blockage or continues to tear, creating a flap of tissue that blocks blood flow in the artery. It strikes without warning, traumatizing survivors. The cause of SCAD is currently unknown. Most doctors are unsure how to treat it.”

Q: What was your own response to the New York Times SCAD article – and to the comments?

♥

In my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease“ (Johns Hopkins University Press), I included much more about how women’s heart disease can differ from men’s in research, diagnostic accuracy, treatments and outcomes. You can ask for this book at your local library or favourite independent bookshop, or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon, or order it directly from my publisher Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

♥

See also:

♥ How I used to describe SCAD. And what I’ve learned since.

♥ “All the SCAD ladies, put your hands up!” (from The Wall Street Journal’s feature on how SCAD patients Laura Haywood-Cory and Katherine Leon succeeded in convincing Mayo Clinic cardiologist Dr. Sharonne Hayes to undertake SCAD research

♥ Watch this 5-minute video of cardiologist Dr. Sharonne Hayes explaining more on this exciting research, plus this 3-minute video from Mayo Clinic explaining SCAD and how survivors Laura and Katherine helped to kick-start this research on the diagnosis they shared.

♥ The SCAD Alliance, a non-profit organization “committed to improving the lives of SCAD patients and their families through education, advocacy, research and support”

♥ SCAD Research is a non-profit fundraising organization, started by Bob Alico, whose wife Judy died from SCAD. When Bob asked the cardiologist what had caused the SCAD that so quickly took Judy’s life, the doctor said he would probably never know the cause because little was understood about SCAD. In the midst of his grief, Bob decided something needed to be done to find answers. He learned that Dr. Sharonne Hayes had started researching SCAD at Mayo Clinic, and also that finding enough funding for this research was critical. In 2011, SCAD Research was established to help fund promising studies; over $800,000 has been raised so far.

♥ The American Heart Association’s official Scientific Statement on Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science

♥ Inspire’s WomenHeart online support groups, including specialty communities for SCAD patients or young cardiac survivors

♥ SCAD Ladies Stand Up: Stories of Patient Empowerment, the special report from Inspire.com and the WomenHeart online support community. It features a number of interesting first-person accounts from SCAD survivors, plus an introduction written by cardiologist Dr. Sharonne Hayes (including a link to a Heart Sisters article listed on the report’s resource page!)

♥ Canadian women diagnosed with Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) are being recruited for a Canadian study based in seven cities nationwide, led by cardiologist Dr. Jacqueline Saw in Vancouver. Ask your cardiologist about participating in the Canadian SCAD Study.

♥ How gender bias threatens women’s health

♥ Cardiac gender bias: we need less TALK and more WALK

♥ How implicit bias in medicine hurts women and minorities

♥ TV News Reporter Jennifer Donelan Survives Heart Attack at Age 36

♥ Be your own hero during a heart attack

♥ Same heart attack, same misdiagnosis – but one big difference

♥ Fewer lights/sirens when a woman heart patient is in the ambulance

I am a 75-year-old woman who has been a coronary patient for 18 months. I’ve been reading your blog off and on during that time, and I feel like I need to share my personal experience:

I was scheduled for a routine D&C 18 months ago, and two days before the procedure, the hospital called with their routine pre-op questions. One of the questions was “Do you have chest pain?” My very casual answer was, “Oh no, well, I do sometimes get chest discomfort when I do my mile walk in the evening.”

I didn’t give it another thought, but the next day my gynecologist called saying the hospital had canceled the surgery until I had been cleared by a cardiologist. (How’s that for being taken seriously when I wasn’t even taking myself seriously!)

I was referred to a cardiologist (who happened to be an interventional cardiologist), and he examined me, did an EKG, took my history, and said, “Everything looks normal, but I think we should do a stress test just to be sure.”

(Understand, I look much younger than my age, I still have a professional job; I play tennis; I am at my appropriate weight; I don’t have hypertension or diabetes, total cholesterol was 200, and I had had a coronary calcium test the year before with a score of 1. In other words, I was a poster child for “no coronary disease.”).

I thought it was much ado about nothing, but I needed that D&C, so I agreed and they set the stress test for 2 days later. Within less than 90 seconds on the treadmill, they stopped the test, the PA conferred with 3 male cardiologists (mine was not in the office that day), and they came in and told me I needed a cardiac cath.

I was stunned. I was planning a trip the next week. I resisted, saying, “Isn’t there another step we can do first, something less invasive?” But they were adamant. It was a Thursday, and they set the cath for Monday and gave me instructions, a phone number, and a bottle of nitro on my way out.

I could hardly believe it. Of course, you can predict the outcome: I had the cath; I had a right coronary artery that was 80% blocked and another smaller artery that was 30% blocked. They put in a stent, and the rest is history, as they say.

My point is that all along the way, my condition (or possible condition) was being taken seriously and treated appropriately by male doctors even when I wasn’t taking it seriously myself (and I live in Charleston, SC–the South not exactly being known for progressive views on feminine causes!)

In addition, I have 2 sisters in 2 other cities and they have both been cared for well and given nuclear stress tests and echocardiograms, etc. with no prodding on their parts–even while neither of them has developed signs of any kind of heart disease. Our father died suddenly of an MI at 56, but that is our only precipitating factor. Perhaps seeing that on a patient history is enough to make a doctor pay attention–I don’t know.

I understand your purpose and completely agree that a woman needs to be assertive and firm in demanding appropriate care in a medical situation just as in so many other situations. But I think it’s also important to point out that many women are getting excellent care from male and female physicians. I personally have no interest in public ranting about gender bias in healthcare. I don’t want to invest in being a victim. I’d rather spend my time making sure I understand the signs of possible conditions I might be faced with and checking in with myself to make sure I’m doing my part to appropriately present my problems and to expect and require that I be treated appropriately (And it’s perfectly acceptable to say, “I need to speak with someone else or your supervisor or the Chief Cardiologist or whoever the next “higher-up” might be.). That’s been my lessons learned and my work over the last 18 months and it has benefits beyond just care in a medical arena.

Judith A. Walker

LikeLike

Hello Judith – your experience is such a great example of what should ideally happen in all cases. If only the stats didn’t clearly suggest that women are in fact at significantly higher risk of this not happening to them.

I don’t consider women who, like me (or like Katherine Leon in this article) have been misdiagnosed in mid-heart attack and sent home from the ER as being “invested in being a victim” because we continue to advocate for women who have not shared your very positive experience.

In fact, yours is the positive outcome we want for all women. That’s not too much to expect.

LikeLike

I had the great good fortune to be seen at the Mayo Clinic by Dr. Robin Smith (a female) who listened carefully to my symptoms, ordered the appropriate testing, and facilitated my quadruple bypass days later.

As an OBGYN physician, I take all cardiac symptoms seriously, and question the patient about TYPICAL female symptoms: indigestion, arm pain, sweats, etc.

Keep ringing the bell, Carolyn, maybe it will awaken the system to women’s heart disease.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dr. Anne, if you have to have bypass surgery, how wonderful to be able to have it done by Mayo physicians!

I think you’re in a uniquely important role since then for the women you see every day both before, during and after pregnancy (as an MD-turned heart patient!) given the known link between pregnancy complications and later heart disease! Thanks for your note…

LikeLike