by Carolyn Thomas ❤️ Heart Sisters (on Blue Sky)

In 2010, Australia’s National Heart Foundation launched what they called a “hard-hitting” Heart Attack Warning Signs awareness campaign. Physicians and cardiac researchers were concerned that too many Australians did not know the common warning signs of a heart attack. They hoped that such an awareness campaign would encourage high-risk patients to quickly call an ambulance if they were having cardiac symptoms. Their Warning Signs campaign explained why this is so critically important:

“When having a heart attack, every minute counts. The longer you wait, the more your heart muscle is damaged. Knowing the warning signs and acting quickly could save your life, or the life of someone close to you.”

Yet Australian researchers(1) reported that during the three years of the campaign, less than half of the patients who had been diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (sudden and dangerously reduced blood flow to the heart muscle) had called an ambulance to get themselves to the Emergency Department. Interestingly, heart patients’ awareness of the heart attack Warning Signs campaign was “not associated with ambulance use.”

Although those researchers reported cardiac symptom awareness was “high or increased” during the 3-year awareness-raising campaign period, there was a significant downward trend in each year following the campaign for most cardiac symptoms.

And worse, the inability to name any heart attack symptom increased in each year following the campaign. The alarming and discouraging conclusion of the study was this:

“Awareness of heart attack symptoms has decreased in the years since the Warning Signs campaign in Australia, with 1 in 5 adults currently unable to name a single heart attack symptom.”

Those shocking results are comparable to the equally shocking results of the American Heart Association’s annual National Survey on Women’s Awareness of Heart Disease, which found women’s awareness was significantly worse than 10 years earlier, despite extensive and expensive Go Red For Women awareness campaigns. Over half of the women surveyed, for example, could not name chest pain as a heart attack symptom. See also: “Women’s Heart Disease: Is it Time To Hang Up The Red Dress?”

Meanwhile, Irish researchers(2) undertook a large study of over 1,900 heart patients also diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome, and reported these outcomes:

- only one-quarter of those heart patients had called an ambulance

- over half had gone initially to their GP’s office to get their symptoms assessed

- just over half of the GP patients continued from their GP’s office to Emergency by self-transport rather than by ambulance (which makes us wonder if the decision NOT to call an ambulance was made by the patient or the GP the patient had just seen)

- 17 per cent arrived directly at the Emergency Department on their own

The strongest predictors in deciding to call for an ambulance included:

- having already survived a previous heart attack (about 1.5 times higher likelihood of calling an ambulance)

- severity of symptoms (patients suffering a cardiac arrest, for example, were 21 times more likely to call an ambulance than non-cardiac arrest patients)

- being a smoker

There are also strong predictors in deciding NOT to call an ambulance, according to Seattle researchers who learned that the delay between the first onset of cardiac symptoms and seeking appropriate help averages about two hours of waiting.(3) That’s a remarkably long time to wait for heart muscle cells to die off.

Some common reasons for that dangerous delay may include:

-because the patient thought that the symptoms would go away

-because the symptoms did not seem severe enough

-because the patient thought that the symptoms were caused by another illness

–because the patient did not even think of calling 911

-because the patient thought that driving their own car to Emergency would be faster

-because the patient had a very busy day planned

-because the patient did not want to be embarrassed by making a fuss in front of Emergency doctors “in case it’s nothing and I would feel like a fool”

Some researchers who specifically study women living with pain also suggest that many of these patients have learned to tolerate a lifetime of different forms of severe pain (from pain that’s unique to women like menstrual cramps, childbirth, endometriosis – or diagnoses that are significantly seen more often in women compared to men – e.g. irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ), chronic pelvic pain, migraine headaches and more).

This unique tolerance to ongoing severe pain is called habituation.

Professor Tali Sharot (at MIT) and Cass Sunstein (at Harvard) explain habituation in their fascinating book Look Again: The Power of Noticing What Was Always There:

“Habituation is the tendency of neurons in the brain to fire less and less in response to things that are constant.”

This reality of habituated pain helps to explain why, after an Emergency Department physician sent me home in mid-heart attack with an acid reflux misdiagnosis, I felt so embarrassed about making a fuss over nothing that my brain began to shrug off my neurons’ alarm signals – and I immediately went back to work.

After that humiliating experience, I attributed all of my severe symptoms to simple indigestion – because a man with the letters M.D. after his name had confidently told me to do so. It took me two full weeks – until the debilitating central chest pain, nausea, sweating and pain down my left arm became so unbearable that I forced myself back to that same Emergency Department. Different doc this time, different (and correct) diagnosis this time: the “widowmaker” heart attack.

And we also know that women, despite having more pain, are less likely to have their pain taken seriously, which in turn can causes extreme reluctance to seek medical care to “make a fuss over nothing”.

Take painful menstrual cramps, for example. Globally, 45-95 per cent of all women of reproductive age suffer from what doctors call “dysmenorrhea”. This particular pain is the leading cause of lost working hours and school absences in females. And when researchers asked women in their studies why they had not sought help for severe period pain (either from their GP or by going to an Emergency Department), their answers ranged from “didn’t think providers would offer help” to “considered symptoms to be tolerable.”(4)

Until women learn to consider extreme pain as neither normal nor tolerable, and until healthcare providers learn to believe women who tell them we’re suffering, researchers will continue to publish studies asking the same questions (and getting the same answers).

No wonder women with cardiac pain wait significantly longer than our male counterparts to seek medical help – including calling for an ambulance.

Finally, there’s another possible barrier to picking up the phone in mid-heart attack and calling 911, and that might be the cost of the ambulance ride.

For example, where I live (on Canada’s beautiful west coast), if I or person nearby calls 911 to take me to the nearest hospital, I will later be sent a bill for $80 from the B.C. Ambulance Service for that trip. My generous extended workplace health insurance benefits don’t cover ambulance transport. And if somebody else calls 911 for me, but I refuse to get into that ambulance, I will be billed $50. This fee discourages people from making frivolous crank 911 calls (and yes, our local 911 dispatch staff do publish a list every January of the year’s stupidest reasons that idiots use to call 911 inappropriately while wasting valuable dispatcher time and paramedic resources (e.g. my neighbour’s wearing too much perfume, or where’s the closest 24-hour pharmacy?) Seriously.

But when you do suspect that your symptoms are genuinely heart-related. please don’t hesitate to call 911.

You know your body. And you know when something is “just not right”.

Remember that chest pain is the most common heart attack sign in both male and female patients (although women often use words like pressure or fullness instead of PAIN). Also remember that cardiac symptoms in women can often come, and then go away, and then come back. As cardiac researcher Dr. Sharon O’Donnell explained, that slow-onset myocardial infarction (MI) is the gradual onset of relatively mild heart attack symptoms, while fast-onset MI describes the immediate onset of sudden, continuous, and severe heart attack symptoms, particularly chest pain.(5)

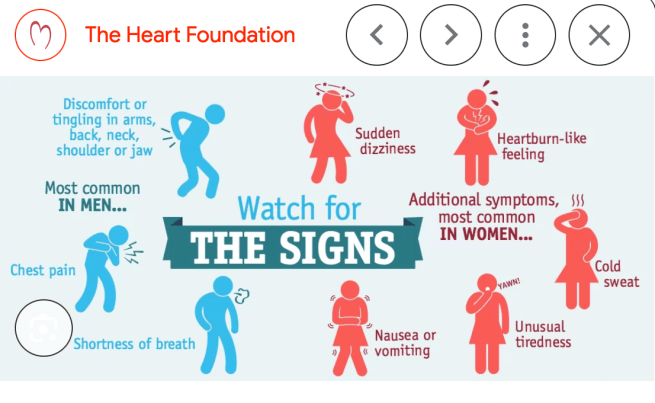

Other common warning signs include the following:

Do not drive yourself to the hospital, and do not let anybody else drive you (unless it’s an extreme emergency (e.g. a blinding blizzard and your cousin next door is a professional snow plow driver). Every paramedic I know has told me that they’d much rather show up and discover the crisis is not a crisis after all, instead of NOT being called and missing out on treating a serious medical issue that could be fatal.

And please please please don’t be like the woman in one of my Heart-Smart Women presentation audiences who told me that she had taken the bus to our Emergency Department in mid-heart attack!

-

Lavery T et al. “Factors Influencing Choice of Pre-Hospital Transportation of Patients with Potential Acute Coronary Syndrome. Emerg Med Australas. 2017 Apr;29(2):210-216.

-

S. Ahern et al. “Factors Influencing Ambulance Usage in Acute Coronary Syndrome”. Irish Medical Journal. February 17, 2022. Vol. 155. #2. P.539.

-

Meischke H et al. “Reasons Patients with Chest Pain Delay or Do Not Call 911.” Ann Emerg Med. 1995 Feb;25(2):193-7

-

Chen CX et al. “Reasons Women Do Not Seek Health Care for Dysmenorrhea. J Clin Nurs. 2018 Jan;27(1-2):e301-e308.

-

O’Donnell, S. et al. “Slow-Onset Myocardial Infarction and Its Influence on Help-Seeking Behaviors.” Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, August 2012. Volume 27 Number 4. Pages 334-344.

♥

NOTE FROM CAROLYN: I wrote more about treatment-seeking delay behaviour in my book, “A Woman’s Guide to Living with Heart Disease” (Johns Hopkins University Press).You can ask for it at your local library or bookshop (please support your favourite independent neighbourhood booksellers) or order it online (paperback, hardcover or e-book) at Amazon – or order it directly from my publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press (use their code HTWN to save 30% off the list price).

See also: Fewer lights/sirens when a woman heart patient is in the ambulance

Imagine this scenario: A person is intelligent, well-informed about her cardiac (and other serious) conditions, high functioning even in stressful situations, and full of skills learned through living with multiple, chronic, potentially life-limiting conditions.

She lives in an area where the ambulance will take her to a regional hospital, owned by one of the largest for-profit health care organizations in the U.S., where patients sometimes wait 10-14 hours in the ED – often in the waiting room and sometimes outside – to receive care (and often much longer if they need in-patient care).

The hospital system has been cited by state and federal agencies for multiple violations related to patient care, some of which have led to serious harm and patients’ deaths, and is currently in the news because yet one more person has died in the ED while awaiting cardiac care. The same hospital system is the defendant in multiple lawsuits and has responded to one of those by claiming that they did not agree to provide quality care when they purchased the hospital system. Some of the doctors who provide care to this well-informed client tell her that she should probably do everything in her power to avoid the ED at this hospital system by relying on her skills in managing her conditions while attempting to contact her cardiology practice and/or “try to make it to another hospital.”

Of course, I am this patient, I recently found myself in this situation, and I ultimately chose not to go to the ED.

If I lived in an area where I could rely on the closest ED for at least adequate care, I would have called for an ambulance. I never, ever, expected to be a person who declined to go to the ED, via ambulance or otherwise, when I knew that emergency care would be best. However, I believed the risks to be too great.

When I contacted my cardiologist’s practice, I was told I made the right choice by following up with their office and trying to manage on an out-patient basis. But did I? I’m still plagued by misgivings over my choice and concerns that the repercussions of that choice will complicate my life and health care for a long time to come.

Would I make the same choice again? I honestly do not know.

LikeLike

Oh, Bren. Your story is a nightmare – and your decision was one that no patient should ever be forced to make. I’m so sorry you had to go through all that. You knew more scary things about this particular hospital than I could even imagine, and you were also advised by your other doctors to avoid going to that hospital’s ED. How on earth is that hospital still allowed to keep their doors open?

It seems that when we’re in a tight squeeze deciding between two extremes (call 911 for transport to a hospital that docs have specifically warned you against, or don’t call 911 and face a potentially dangerous outcome) you made the only decision that makes sense, given what you know and what you’ve been advised by docs who know, too.

What’s most shocking to me is that one of the wealthiest countries in the world continues to tolerate substandard for-profit hospital systems like that one, where patients actually need to weigh the personal risks of going to a hospital for emergency care!?!?!

It seems clear to me that you made the only call that any reasonable person would have made – and as your own cardiologist practice reassured you as well. I hope that the follow-up outpatient care you’re receiving from your practice helps you feel better, both now and into the future. Please don’t torture yourself for one more minute with misgivings about making a choice to avoid going to a facility whose owners claimed they did “not agree to provide quality care when they purchased the hospital system”.

What I know is that we all make the best decisions we know how to make based on the information we have at the time – and it seems like you had an avalanche of damning information that should scare off every patient facing the same choice you did. The only other option (and I don’t know if this even exists where you live if your local paramedics are forced to take patients to one specific hospital) is the option of telling the 911 dispatcher that you’ll need the ambulance to take you to ABC Hospital – one that your cardiologists can recommend.

Take care and good luck to you. . .❤️

LikeLike

Carolyn, I appreciate your thoughtful reply, empathy, and understanding of the nuances involved in my situation–a situation shared by many thousands of people in my region.

Yes, indeed, it is “shocking…that one of the wealthiest countries in the world continues to tolerate substandard for-profit hospital systems like that one….”

Many voices via many different avenues have been demanding attention and change, yet the hospital system continues to grow more and more profitable at the expense of patient care. One of those voices represents my county’s EMS system, which is obligated not only to take patients who call 911 to that particular hospital (despite patients begging for another option) but also to remain with patients until they’ve been appropriately triaged, which can take quite a long time in some circumstances.

I can only imagine the moral distress that these first responders experience–and that of the understaffed ED team members, who are working to do their best in a very harsh and unforgiving care system.

Thank you for expanding your post about the importance of heart patients calling an ambulance to access emergency care to include the quandary that some of us face when trying to access the care we need.

And, as always, thank you for your dedication to educating and supporting women who live with heart disease! You’ve been a part of my lifeline for over ten years now.

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind words, Bren. This is a predictably bad scenario when a country allows wealthy hedge fund investors to own hospitals. It is then about money and profit, not patient care. Your story is certainly one of the worst I’ve heard from any of my American readers.

I’m so glad you also mentioned the stress among EMS staff (especially during what they call those “offload delays” you described). It’s not only an appalling waste of the paramedics’ time, but it means 911 dispatchers have few or NO available ambulances to send out in answer to new urgent calls for help if those ambulances are all parked in some hospital driveway waiting to safely hand off their latest patient. I wrote more about this stress in another article: :

“I know that my paramedic friends have a hugely challenging job to do. Every day, they deal with horrific traumatic injuries, family tragedies, overflowing Emergency Departments, offload delays, ambulance diversion, staffing shortages, extreme stress and so much more.”

Take care – keep healthy! ❤️

LikeLike

Years ago I went to hospital with a badly broken ankle. I was billed about $300.

After explaining that I couldn’t work with the cast on for 6 weeks and had no income, the province (Alberta) agreed not to dun me (meaning: “to demand payment of a debt“)

I was told to get better and pay when I was back at work. However I continued to be billed monthly. Now the bill for taking an ambulance is $385.

It’s easy to see how people would hesitate to call one.

LikeLike

Yoiks! When I got to the part about the Alberta hospital telling you ‘Get better and pay when you’re back at work’, I was touched by such a profound act of compassion.

But then I read the rest.

Whoever the hospital employee was who assured you “Pay when you’re back at work…” was a liar. Unless they had clearly negotiated a bill payment plan (and had you signed that agreement) which included interest payments or additional expenses, they could have done the right thing – but chose not to.

LikeLike

…..Me lying on the ground with a severely broken arm telling my son: “Wait, don’t call 911. Let me see if I can sit up and you can drive me to the hospital.”

Followed by excruciating pain and almost passing out.

”OK, Call 911 but tell them I don’t need a fire truck, just an ambulance.”

LikeLike

Oh, Jill. I can truly imagine that response! Not wanting to make a fuss, wanting to avoid being embarrassed or wasting the very valuable time of first responders (while they should be out helping those far more urgent cases…) I hope you arrived at the hospital quickly and safely – and had that arm set properly!

Take care. . .❤️

LikeLike